Cognitive Decline in Patients on an Acute Geropsychiatric Unit

Abstract

The authors compared patients in a geropsychiatric unit who showed marked cognitive decline during hospitalization with those who did not. Patients who declined in cognitive function were older, were more likely to have a diagnosis of dementia, and were more anergic on admission. These patients were also discharged to more restrictive living environments. The subgroup of demented patients who declined in cognitive function were also older and improved less on anxiety and depression.

Geropsychiatric hospitalization is required for older patients with severe psychiatric symptoms who are unable to function on their own and consequently become a danger to themselves or a burden to others. When less intensive interventions have failed, inpatient care is often the best alternative for these patients. However, psychiatric hospitalization is not always without problems. Among the negative aspects are the associated risk of nosocomial infections, disruption of the patient's daily routine, isolation from family and friends, the high cost of inpatient care, and uncertainty as to whether the benefits last beyond hospitalization. In this era of health cost management, it is important to identify those patients who may not benefit from inpatient care and to determine what factors are associated with lack of improvement. In an outcome study of geropsychiatric inpatients by Kujawinski et al.,1 a notable percentage of the elderly patients (10%) showed marked decline in cognitive function.

We hypothesized that the patients who show cognitive decline are older, have a diagnosis of dementia, and have more medical problems, whereas patients who cognitively improve or remain the same are those with the more treatable psychiatric symptoms such as psychosis, depression, and anxiety. We reasoned that the older patients with dementia or multiple medical problems are more negatively affected by environmental changes and pharmacologic side effects. We also suspected that the cognitively intact patients with psychiatric symptoms improve because they are better able to attend and focus on testing after their psychiatric symptoms remit.

We were unable to find any study that systematically examined possible predictors of such cognitive deterioration during psychiatric hospitalization. In our study, we evaluated geropsychiatric inpatients at the Houston Veterans Affairs Medical Center (HVAMC) whose Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores decreased from admission to discharge to determine variables associated with negative change in cognitive status.

METHODS

We identified all patients admitted to the HVAMC 20-bed geropsychiatry unit between October 1993 and May 1995 whose MMSE scores declined by 3 points or more during their hospital course (group 1). This cutoff was determined by slightly modifying the Kujawinski et al. criteria, where a drop of more than 3 points on the MMSE was categorized as marked cognitive decline.1 The validity of this criterion in our population was examined by computing a paired t-test between pre and post MMSE scores (t=–4.59, df=280, P<0.001; paired-difference χ2=–1.37, SD=5.02, 90% confidence interval=–0.88 to –1.86). Given that our sample's mean difference of 1.37 was highly significant, we felt the clinical significance of a 3-point change in MMSE score was supported. The remaining patients, who did not show marked cognitive decline, were used as a control group (group 2). We also examined the subgroups of demented patients who showed marked cognitive decline (group 1D), and demented patients who did not show marked cognitive decline (group 2D).

All patients received a comprehensive multidisciplinary evaluation by a team of two geriatric psychiatrists, a geropsychologist, psychiatric nurses, a social worker, and a physician's assistant. The evaluation included a comprehensive psychiatric, medical, and social history, a physical examination, a serum chemistry panel, a complete blood count, an electrocardiogram, an electroencephalogram, and a computerized tomographic brain scan. On admission and discharge, the attending psychiatrist rated each patient on a standardized battery consisting of the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE);2 the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (Ham-D);3 the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS),4 including subscales of Activity (ACTV), Anxiety/Depression (ANDP), Anergy (ANER), Hostility (HOS), and Thought Disorder (THOT); the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI);5 and the Rating Scale for Side Effects (RSSE).6 Our interrater reliability, measured by intraclass correlation coefficients, was 0.60 for the BPRS, 0.76 for the CMAI, and greater than 0.9 for the MMSE, Ham-D, and RSSE.

Within 3 weeks of each patient's discharge, a consensus conference of the two geriatric psychiatrists, the geropsychologist, and other team members established Axis I and Axis II psychiatric diagnoses by DSM-III-R (and later DSM-IV).7,8 Individuals who had multiple cognitive deficits manifested by both memory impairment and either aphasia, apraxia, agnosia, or disturbances in executive functioning were considered to have dementia. We documented all medical problems causing disability or being actively treated on Axis III and recorded the total number as an index of medical burden for each patient. All patients received multidisciplinary treatment, including pharmacotherapy, a structured milieu, and family education.

Data were analyzed by using chi-square and discriminant analyses to compare group 1 with group 2 and group 1D with group 2D. Discriminant analyses were used to compare age, medical burden, length of stay, number of medications, admission rating scale scores, and change in rating scale scores from admission to discharge. Chi-square was used to compare race, marital status, education, gender, admission living arrangements, discharge living arrangements, change in living arrangements from admission to discharge, types of medications, and primary diagnoses.

RESULTS

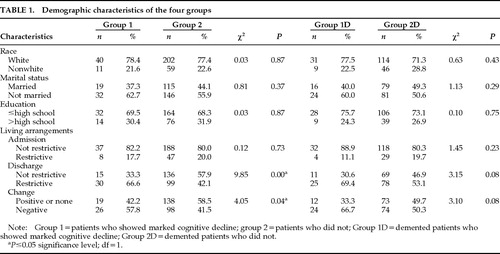

Of the 378 admissions between October 1993 and May 1995, 66 patients were excluded from the study because of incomplete data. Of the remaining 312 patients, group 1 consisted of 51 patients who declined by 3 points or more on MMSE scores from admission to discharge, and group 2 consisted of the other 261 patients. Overall, 13.5% of the patients in the study showed a decline in cognitive function. The mean age (±SD) of the patients in group 1 (all male) was 74.1±7.1 years; the mean age of patients in group 2 (97% male) was 71.3±5.6 years (t=2.95, df=278, P=0.004). The mean number of medical diagnoses per patient was 4.1±2.9 in group 1 and 4.3±2.8 in group 2. The average lengths of stay for group 1 and group 2 were 40±26.5 and 34±29 days, respectively. No significant differences were found in the lengths of stay. Table 1 shows group demographic characteristics, admission living arrangements, discharge living arrangements, change in living arrangements from admission to discharge, and the respective chi-square values. Group 1 patients showed a significant negative change in living arrangements from admission to discharge when compared with group 2 patients (the group 1 patients having been discharged to more restrictive settings).

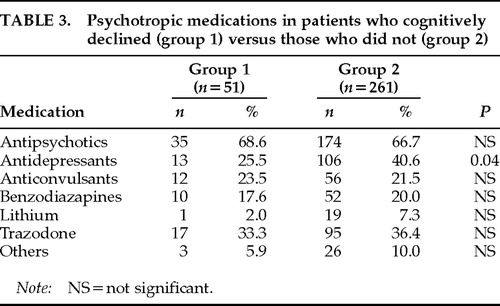

Table 2 shows the primary diagnoses of the patients in group 1 and group 2. Overall, the patients in group 1 had an average of 2.3±1.1 psychiatric diagnoses and patients in group 2 had an average of 2.4±1.1 psychiatric diagnoses. The patients in group 1 were significantly more likely to have a diagnosis of dementia than the patients in group 2 (χ2=2.2, P=0.03). There was no significant difference in the mean number of psychotropic medications per patient between group 1 and group 2 (1.9±1.0 vs. 2.1±1.0); however, patients in group 2 were prescribed significantly more antidepressants other than trazodone (χ2=2.03, P=0.04; Table 3).

Stepwise discriminant classification analyses were performed to determine the optimal combination of variables that would predict significant cognitive decline at discharge. Separate analyses were performed using either admission variables or change score variables (admission score minus discharge score) as the predictor variables. The criterion variable for all stepwise discriminant analyses was MMSE decline of 3 or more points. A priori probabilities of group membership were adjusted to reflect the differing group sizes of the criterion variable: P (group 1)=0.20; P (group 2)=0.80. F-to-enter criterion was 3.84, and F-to-remove criterion was 2.91.

The discriminant classification analysis using admission predictor scores included age, the BPRS admission subscale scores, GAF admission score, Ham-D admission score, medical burden, and length of stay as predictor variables. The discriminant function for the whole sample correctly classified 84% of the patients. Only age significantly contributed to the discriminant function (Wilks' λ=0.96, P=0.002). Examination of the eigenvalue (0.04) and canonical correlation (0.20) for the discriminant function indicates that much variation exists between groups and the association between the discriminant score and the groups is small.

The stepwise discriminant classification analysis was also performed to determine the optimal combination of change score variables that would predict significant cognitive decline at discharge based on change scores (admission minus discharge scores). The predictor variables for the analyses were the BPRS subscale change scores and Ham-D change score. The discriminant function for the whole sample correctly classified 84% of the patients. Only the BPRS subscale Anergy (ANER) significantly contributed to the discriminant function (Wilks' λ=0.94, P=0.001). Examination of the eigenvalue (0.06) and canonical correlation (0.24) for the discriminant function indicates that much variation exists between groups and the association between the discriminant score and the groups is small.

Because the prevalence of dementia was higher in the group that declined in cognitive function than in the group that did not, we did a subgroup analysis of the demented patients who deteriorated cognitively versus those who did not.

Table 1 shows group demographic characteristics, admission living arrangements, discharge living arrangements, change in living arrangements from admission to discharge, and the respective chi-square values. Patients in both group 1D and group 2D had an average of 2.6±1.1 psychiatric diagnoses and were prescribed an average of 2.0±1.0 medications. No significant differences in primary psychiatric diagnosis or class of medication were found between group 1D and group 2D.

The stepwise discriminant classification analyses for admission score predictor variables and change score predictor variables were repeated with the subgroup of patients with a diagnosis of dementia. When using admission scores as predictor variables, the discriminant function correctly classified 81% of the patients. Only age significantly contributed to the discriminant function (Wilks' λ=0.95, P=0.005). Examination of the eigenvalue (0.06) and canonical correlation (0.23) for the discriminant function indicates that much variation exists between groups and the association between the discriminant score and the groups is small. When change scores were used as predictor variables, the discriminant function correctly classified 79% of the patients. The BPRS ANDP (anxiety/depression) and ANER (anergy) subscales significantly contributed to the discriminant function (ANER: Wilks' λ=0.94, P<0.001; ANDP: Wilks' λ=0.92, P<0.001). Examination of McNemar's chi-square statistic shows that the addition of ANDP to the discriminant function significantly increases the classification accuracy of the function (χ2=204.80, P<0.05). Examination of the eigenvalue (0.09) and canonical correlation (0.29) for the discriminant function indicates that much variation exists between groups, but association between the discriminant score and the groups is larger than that yielded by any other discriminant analysis.

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to examine in detail older psychiatric inpatients who show cognitive decline. We found that 13.5% of the patients in our geropsychiatry unit declined in cognitive function. In general, the patients who deteriorated were significantly older and more likely to have a diagnosis of dementia. Patients who declined cognitively also showed a significant negative change in their living arrangements: after hospitalization they were discharged to more restrictive settings than patients who did not show such cognitive decline. When only patients with a diagnosis of dementia were analyzed, the demented patients with marked cognitive decline were found to be significantly older and to improve less on anxiety and depression when compared with the demented group that did not cognitively decline.

Patients who showed cognitive decline had significantly more primary diagnoses of dementia, yet when only demented patients were analyzed, few significant differences were found between the two groups. It may be that a change in milieu and disruption of activities differentially affect certain demented patients who do not benefit from the structure provided by hospitalization, causing their cognitive decline. However, it is important to note that in a prior study, we found that a majority of the most severely demented patients benefit from psychiatric hospitalization.9 Further research is necessary to identify and examine which older demented patients decline and why.

Our study has limitations. We looked at patients in a Veterans Affairs geropsychiatry unit. Because these patients are almost all males who tend to have multiple medical, psychiatric, psychological, and social problems related to low socioeconomic status, this sample cannot be generalized to the overall geropsychiatric population. Furthermore, the discriminant analysis was not cross-validated in another sample and therefore limits the generalizability. It may be that other variables that were not measured play a greater role.

All patients received multimodal treatment, so the possible contributions of particular treatments to cognitive decline could not be assessed. For example, most patients were on multiple medications, perhaps obscuring a negative effect on cognitive functioning of a particular medication or combination of medications. The rating scales used to assess patients may have been limited in their ability to detect variables associated with cognitive decline. Factors such as onset and duration of psychiatric symptoms, family involvement, psychosocial relationships, effect of psychotherapy, and impact of change in the patient's daily activities were not assessed by these scales. Future research investigating geriatric patients who decline during psychiatric hospitalization should address these factors more systematically.

Because most of the patients in our geropsychiatry unit showed improvement in cognitive function at discharge, the 13.5% who declined in cognitive function merit close attention. In their study of a geropsychiatric unit, Kujawinski et al.1 found that 10% of the patients showed marked cognitive decline at discharge. Thus, it appears that a consistent percentage of patients decline in cognitive function with inpatient care. A decline in cognitive function has real-life implications, since these patients are being discharged to more restrictive settings. Given the current emphasis on cost-benefit analysis for health care, it will become increasingly necessary to identify patients at admission who are at risk for negative outcome so that either hospitalization can be avoided or special interventions to prevent decline can be implemented during their hospital stay.

|

|

|

1. Kujawinski J, Bigelow P, Diedrich D, et al: Research considerations: geropsychiatry unit evaluation. J Gerontol Nurs 1993; 19:5–10Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR: “Mini-Mental State”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975; 12:189–198Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960; 23:56–62Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Overall JE, Gorham DR: The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychol Res 1962; 10:799–812Google Scholar

5. Cohen-Mansfield J, Marx MS, Rosenthal AS: A description of agitation in a nursing home. J Gerontol 1989; 44:M77–M84Google Scholar

6. Åsberg M, Cronholm B, Sjoqvist F, et al: Correlation of subjective side effects with plasma concentrations of nortriptyline. Br Med J 1970; 4:18–21Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd edition, revised. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1987Google Scholar

8. American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

9. Bakey AA, Kunik ME, Orengo CA, et al: Outcome of psychiatric hospitalization for low-functioning demented patients. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 1997; 10:55–57Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar