Quetiapine (Seroquel) in the Treatment of Psychosis in Patients With Parkinson's Disease

Abstract

Psychoses are a common clinical problem in patients with Parkinson's disease. Treatment with typical neuroleptics or withdrawal of antiparkinsonian drugs may improve mental symptoms but will worsen the parkinsonism. Quetiapine (Seroquel), ICI 204,636, is a novel antipsychotic medication with a low potential for producing extrapyramidal side effects. In this open-label clinical study of 2 patients with Parkinson's disease, treatment with Seroquel successfully controlled psychotic symptoms without worsening of motor disability.

Psychosis is one of the most disabling psychiatric disorders associated with Parkinson's disease (PD) and a significant contributor to nursing home placement.1 Treatment of psychotic symptoms, including delusions and hallucinations, is difficult. Traditional treatment strategies, such as the withdrawal of anti-PD medications and/or the use of typical dopaminergic antagonists, are often unsatisfactory and lead to an increase in motor disability.

Quetiapine (ICI 204,636) is an atypical antipsychotic agent that interacts with multiple neurotransmitter brain receptors, with a higher affinity for serotonin 5-HT2 than dopamine D1 or D2 receptors.2 Clinical studies have demonstrated that quetiapine is an effective antipsychotic agent with a low incidence of extrapyramidal, anticholinergic, and cardiovascular side effects. There is no evidence of agranulocytosis associated with quetiapine. Such an agent could represent a significant advance in the treatment of psychosis in PD patients.

Our intent in this study was to evaluate the utility and safety of quetiapine in the treatment of psychosis in PD patients. We enrolled 2 patients with idiopathic PD and psychosis in an ongoing 52-week open-label clinical trial of quetiapine (Seroquel). Both patients were neuroleptic-naive and were stabilized on carbidopa/levodopa for motor symptoms before study enrollment. Quetiapine was started at 25 mg/day and was gradually increased as clinically indicated (or as tolerated) until psychotic symptoms were no longer present. Throughout the study, the dose of carbidopa/levodopa was held constant. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) and a 7-point Clinical Global Impressions–Severity of Illness Scale (CGI-S) measured the severity of psychiatric symptoms.3,4 The Simpson Scale, the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS), and the Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) measured the severity of motor abnormality.5–7 Cognitive status was assessed by means of the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE).8 In addition to the assessment of adverse events, physical examinations, vital signs, weights, electrocardiogram (ECG) and laboratory studies (complete blood chemistry, blood count, thyroid function tests, and urine analysis) were performed at screening and regularly throughout the study.

Case Report

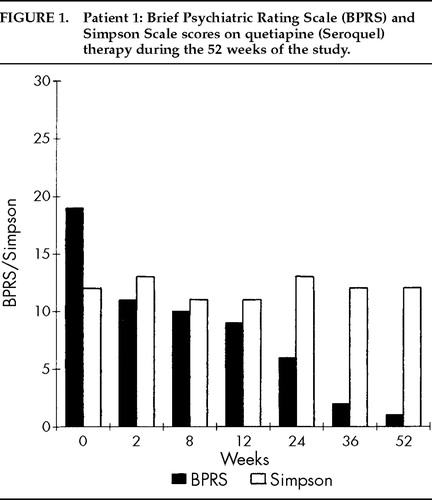

Patient 1. A 74-year-old man with a 2-year history of idiopathic PD and a long-standing history of affective bipolar disorder (well controlled on divalproex sodium) was referred for psychiatric evaluation because of marked visual hallucinations and persecutory delusions. His past medical history was also significant for hypertension and congestive heart failure. His medication regimen included carbidopa/levodopa 100/400 mg/day, furosemide 20 mg/day, doxazocin mesylate 2 mg/day, and divalproex sodium 1,250 mg/day (with valproate blood level ranging between 78 and 98 mg/l). The patient reported seeing people breaking into his backyard to steal his canoe and other belongings, and he was puzzled as to why his dog was not barking or attacking the intruders. He had called the police department on multiple occasions to arrest the intruders. His clinical assessment results included BPRS total score of 19 (where 0 on severity scale indicates absence of symptomatology), CGI-S score of 5 (“markedly ill”), Simpson Scale total score of 12 (10 items, with 1–5 severity scale for each item), AIMS total score of 0 (where 0 on severity scale indicates absence of tardive dyskinesia), UPDRS (motor examination section) total score of 14 (14 items, with 0–4 severity scale for each item), and MMSE total score of 28/30. Urine analysis and routine blood tests (chemistry, cell count, thyroid, VDRL, B12, and folate) were all within normal limits. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain revealed mild cortical volume loss, with ischemic/degenerative changes in periventricular white matter and basal ganglia. ECG showed normal sinus rhythm with evidence of old inferior infarct.

Quetiapine was introduced at 25 mg/day and gradually increased to a maximum dose of 400 mg/day over the subsequent 12 weeks. Delusions and hallucinations resolved almost completely, and quetiapine was well tolerated by the patient, without any worsening in PD. He maintained his improved mental condition and motor function throughout week 52. At completion of study, BPRS total score was 1, CGI-S score was 1 (“not at all ill”), Simpson Scale total score was 12, AIMS total score was 0, UPDRS (motor examination section) total score was 6, and MMSE total score was 29/30. Complete scores on BPRS and the Simpson Scale during the 52 weeks of study are summarized in Figure 1.

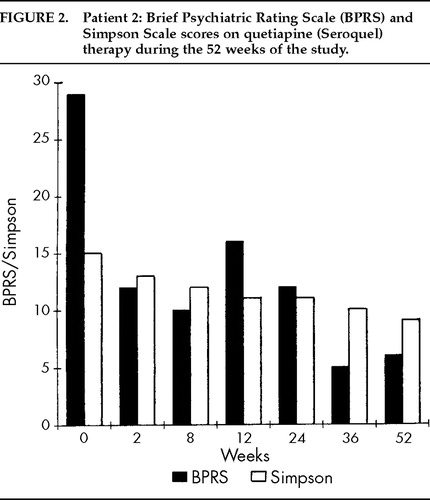

Patient 2. A 74-year-old woman who was diagnosed at age 68 as having idiopathic PD, was referred for psychiatric evaluation because of visual and auditory hallucinations and paranoid delusions. Her past medical history included hypothyroidism, hypertension, peptic ulcer disease, and idiopathic thrombocytopenia purpura, and she had suffered several falls as a result of PD-related postural instability. Her medication regimen was carbidopa/levodopa 75/300 mg/day, selegiline hydrochloride 10 mg/day, levothyroxine 0.05 mg/day, lisinopril 5 mg/day, and omeprazole 20 mg/day. The patient reported seeing animals running in her apartment and hearing her deceased husband whistling at night. In addition, she exhibited mild conceptual disorganization, mild cognitive and memory deficits, paranoid ideations, and anxiety symptoms. Her clinical assessment results included BPRS total score of 29, CGI-S score of 5, Simpson Scale total score of 15, AIMS total score of 0, UPDRS (motor examination section) total score of 19, and MMSE total score of 25/30. Urine analysis and routine blood tests (chemistry, cell count, thyroid, VDRL, B12, and folate) were all within normal limits, except for a platelet count of 78×1,000/mm3. ECG was normal. Brain imaging studies with SPECT using technetium-99m (Ceretec™) disclosed a symmetrical decrease in radiopharmaceutical uptake in bilateral temporal and posterior parietal regions, suggestive of dementia. Brain computed tomography scan showed moderate, diffuse cortical volume loss.

Quetiapine was introduced at 25 mg/day and gradually increased to a maximum dose of 200 mg/day over the following 16 weeks. The patient's mental condition improved dramatically without significant change in parkinsonism or emergence of any significant side effects. Despite a gradual cognitive and memory deterioration due to a dementing process, she remained free of delusions and hallucinations over the subsequent 36 weeks. At completion of study, BPRS total score was 6, CGI-S score was 2 (considered as “borderline ill”), Simpson Scale total score was 9 (item number 1 for “gait” assessment was considered “not ratable” because of a gait disability related to previous hip fracture), AIMS total score was 0, UPDRS (motor examination section) total score was 23, and MMSE total score was 14/30. Complete scores on the BPRS and Simpson Scale during the 52 weeks of study are summarized in Figure 2.

DISCUSSION

Psychoses occur in up to 30% of patients with PD.9 Such psychotic disturbances are more common in PD patients with concomitant dementia (up to 80%) than in those without concomitant dementia (up to 20%).10 Several open-label studies using clozapine have shown that it is a promising treatment for PD associated psychosis.9 However, the risk of agranulocytosis, the inconvenience of the weekly blood draws, and the inability to tolerate other side effects have limited the use of clozapine. Risperidone has been successfully used to control psychoses, but its effects on parkinsonism have received negative reviews.11 One open-label study has reported olanzapine to be a well tolerated and effective treatment for dopaminomimetic psychosis in nondemented patients with PD,12 but its safety and efficacy in PD patients with concomitant dementia are unclear. Therefore, introduction of other novel antipsychotic medications with low EPS profile and low anticholinergic properties may provide alternative treatment options, especially in PD patients with dementia.

Quetiapine is a novel dibenzothiazepine derivative, with a preclinical profile consistent with an atypical antipsychotic, developed for the treatment of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. It interacts with multiple neurotransmitter receptors in the brain with a higher affinity for serotonin 5-HT2 (IC50=148 nM) than dopamine D1 (IC50=1,268 nM) or D2 (IC50=329 nM) receptors.2,13 In animal tests predictive of EPS, quetiapine is distinct from standard antipsychotic medications and produces only weak catalepsy at effective dopamine D2-blocking doses. Unlike standard agents, quetiapine does not produce depolarization inactivation of nigrostriatal dopamine neurons, does exhibit limbic selectivity, and produces minimal dystonic liability in haloperidol-sensitized and drug-naive cebus monkeys after acute and chronic administration. Compared with typical antipsychotic agents, quetiapine has considerably less muscarinic cholinergic (IC50>10,000 nM) and alpha-1 adrenergic (IC50=90 nM) receptor antagonist properties.2,13 Quetiapine is well tolerated, and treatment has not been associated with any cases of agranulocytosis or problematic changes in cardiovascular parameters.14,15

This open-label pilot study demonstrated successful use of quetiapine in the treatment of 2 neuroleptic-naive PD patients (1 without dementia, 1 with dementia) who suffered from psychosis. Both patients were considered “markedly mentally ill” (as measured by CGI-S scale) and required treatment with an antipsychotic agent. Quetiapine improved the psychiatric state dramatically (as measured by BPRS and CGI-S scale) without significant adverse effects on parkinsonism (as measured by the Simpson scale and UPDRS) or medical condition. The observed absence of motor toxicity in these patients, who are most vulnerable to EPS, is in line with the lack of EPS observed in schizophrenic patients treated with quetiapine. Further research, using double-blind placebo-controlled techniques, to determine the efficacy and safety of quetiapine in patients with PD is clearly indicated.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank David Agle, M.D., at Case Western Reserve University, and Lisa Arvanitis, M.D., and Jeffrey Goldstein, Ph.D., at Zeneca Pharmaceuticals, for their review of this manuscript. This research was sponsored by Zeneca Pharmaceuticals, which manufactures Seroquel. An abstract was presented in the poster session at the International Academy for Biomedical and Drug Research meeting, Rome, Italy, April 4–6, 1997.

FIGURE 1. Patient 1: Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) and Simpson Scale scores on quetiapine (Seroquel) therapy during the 52 weeks of the study.

FIGURE 2. Patient 2: Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) and Simpson Scale scores on quetiapine (Seroquel) therapy during the 52 weeks of the study.

1. Goetz CG, Stebbins GT: Risk factors for nursing home placement in advanced Parkinson's disease. Neurology 1993; 43:2227–2229Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Hirsch SR, Link CGG, Goldstein JNM, et al: ICI 204-636: a new atypical antipsychotic drug. Br J Psychiatry 1996; 168(suppl 29):45–56Google Scholar

3. Overall JE, Gorham DR: The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychol Rep 1962; 10:799–812Crossref, Google Scholar

4. Guy W: Clinical Global Impressions, in ECDEU: Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology (revised). Washington, DC, US Department of Health, Education and Welfare, 1976, pp 76–338Google Scholar

5. Simpson GM, Angus JW: A rating scale for extrapyramidal side effects. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 1970; 212:11–19Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Guy W: Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale, in ECDEU: Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology (revised). Washington, DC, US Department of Health, Education and Welfare, 1976, pp 534–537Google Scholar

7. Lang AE, Fahn S: Assessment of Parkinson's disease, in Quantification of Neurologic Deficit, edited by Munsat TL. Boston, Butterworth, 1989, pp 285–309Google Scholar

8. Folstein MF, Folstein S, McHugh PR: “Mini-Mental State”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975; 12:189–198Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Musser WS, Akil M: Clozapine as a treatment of psychosis in Parkinson's disease: a review. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1996; 8:1–9Link, Google Scholar

10. Wolters E, Tuynman-Qua HG: Dopaminomimetic psychosis: the role of atypical neuroleptics, in Pautas actualis en el tratamiento médico y quirúrgico de la enfermedad de Parkinson, edited by Alberca R, Ochoa JJ. Barcelona, Inter-Congres, 1995, pp 257–268Google Scholar

11. Rich SS, Friedman JH, Ott BR: Risperidone versus clozapine in the treatment of psychosis in six patients with Parkinson's disease and other akinetic-rigid syndromes. J Clin Psychiatry 1995; 56:484–485Medline, Google Scholar

12. Wolters E, Jansen ENH, Tuynman-Qua HG, et al: Olanzapine in the treatment of dopaminomimetic psychosis in patients with Parkinson's disease. Neurology 1996; 47:1085–1087Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Richelson E: Preclinical pharmacology of neuroleptics: focus on new generation compounds. J Clin Psychiatry 1996; 57(suppl 11):4–11Google Scholar

14. Saller CF, Salama AL: Seroquel: biochemical profile of a potential atypical antipsychotic. Psychopharmacol (Berl) 1993; 112:285–292Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Fabre LF, Arvanitis L, Pultz J, et al: ICI 204-636, a novel atypical antipsychotic: early indication of safety and efficacy in patients with chronic and subchronic schizophrenia. Clin Ther 1995; 17:366–378Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar