Neuropsychiatric Features of Frontotemporal Dementia

Abstract

Neuropsychiatric features characterize frontotemporal dementia (FTD). The authors evaluated the neuropsychiatric features of 53 FTD patients and retrospectively applied the Consensus Criteria for this disorder. Only one-third of the patients met Consensus Criteria for FTD on presentation. Most had early disengagement with poor insight; however, more than half retained socially appropriate interpersonal conduct and emotional expression. Supportive features, including compulsive-like acts and speech changes, were common presenting features, and 20% developed the Klüver-Bucy syndrome on 2-year follow-up. Consensus Criteria for FTD offer guidelines for diagnosis, but further refinement is needed, particularly for patients who lack early changes in social interpersonal conduct.

Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) is a clinicopathological syndrome with prominent behavioral symptoms and progressive degeneration of the frontal lobes, anterior temporal lobes, or both. FTD is not a rare disorder and is often misdiagnosed. FTD patients make up about 10% of all patients with dementing diseases.1–3 Because FTD is usually a presenile onset disorder, among dementia patients with age at onset of less than 65 years FTD accounts for approximately 20% of neurodegenerative dementias.1–4

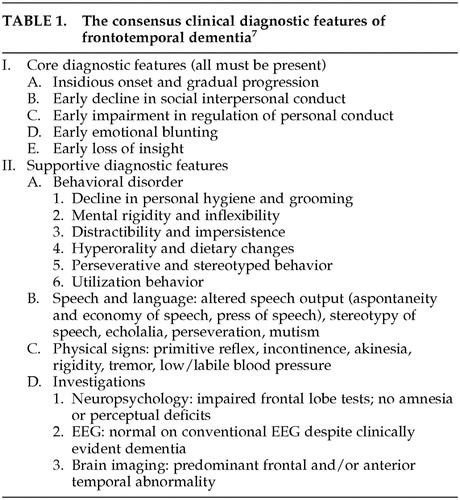

In FTD, neuropsychiatric changes are the most prominent symptoms, and they usually precede or overshadow cognitive disabilities.1,2,5 Suspicion of FTD arises when there is a gradual personality change and frontotemporal abnormalities on neuroimaging, particularly frontotemporal hypometabolism.6 Clinical criteria for diagnosing FTD include the original Lund and Manchester criteria and the more recent Consensus Criteria for FTD (Table 1).3,7 Core behavioral features of the Consensus Criteria are impaired social interactions, impaired personal regulation, emotional blunting, and loss of insight.7 FTD patients also have a range of other behaviors considered “supportive diagnostic features” by Consensus Criteria (Table 1). These criteria have not been evaluated in a large number of FTD patients previously diagnosed by using Lund and Manchester guidelines. We retrospectively apply the behavioral features from the Consensus Criteria to 53 patients previously diagnosed with FTD and review the literature on the noncognitive neuropsychiatric manifestations of this disorder.

METHODS

Subjects

The participants in this study were enrolled in neurobehavioral clinics at the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) and the Veterans Affairs (VA) Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System. These community-based, moderately impaired patients underwent a complete examination including neuroimaging. The survey excluded patients who had other medical, neurologic, or psychiatric disorders or medications that could account for their mental status findings.

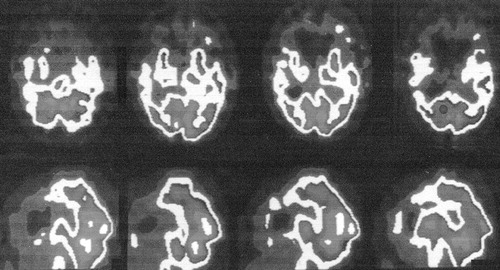

The diagnosis of FTD was based on clinical criteria plus changes on functional neuroimaging. The 53 FTD patients met clinical criteria recommended by the Lund and Manchester groups.3 All of the FTD patients presented with behavioral complaints plus symptoms of behavioral disinhibition, loss of social or personal awareness, or disengagement. Patients with the initial syndrome of primary progressive aphasia were specifically excluded from this report.7 The diagnosis of FTD also required the presence of frontal hypoperfusion on single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), as illustrated in Figure 1, or hypometabolism on positron emission tomography (PET). The presence of frontally predominant atrophy on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was supportive but not necessary for the diagnosis.

Dementia severity was based on two dementia severity measures, the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (CDR).8,9 The MMSE was not considered sufficient to assess dementia severity because of its emphasis on language and orientation, hence the addition of the CDR. Although the CDR is dependent on memory impairment, it is minimally dependent on language, visuospatial, and other cognitive deficits and includes an assessment of functional impairment.

Procedures

The Consensus Criteria guidelines were characterized into 13 behavioral items. Only the laboratory criteria (neuropsychological tests, electroencephalograms, brain imaging) were excluded. Two investigators retrospectively and independently evaluated the 13 behavioral items as either present or not present, on the basis of clinical history, an initial examination, and a 2-year follow-up examination. Detailed records were kept on these patients, who were eventually included in a dedicated FTD program. Absence of a description of the symptom was evaluated as “not present.” The two investigators arrived at a final determination by consensus after discussion of each of the 53 patients. The investigators had nearly complete agreement regarding the presence or absence of four of the five core symptoms. Ascertaining the presence of emotional blunting was more difficult; it relied on apparent lack of emotion on examination and caregiver reports of loss of empathy, sympathy, or feelings of embarrassment.

RESULTS

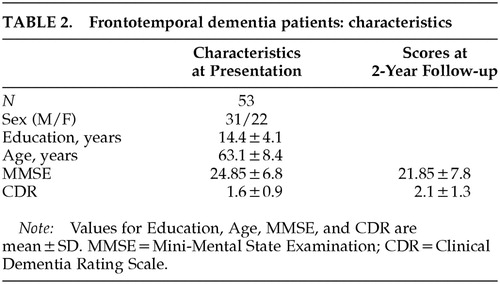

The characteristics of the FTD patients are summarized in Table 2. The gender ratio is skewed toward males because of the number of VA patients included in this study. Thirteen patients came from the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System and 40 from UCLA Medical Center.

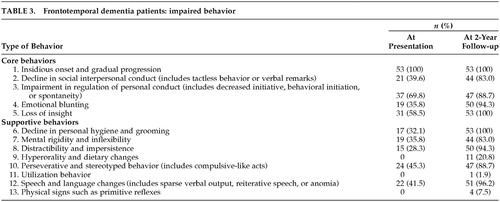

Evaluation of the Consensus Criteria revealed several findings (Table 3). Only 17 patients (33%) had all five of the core features on initial presentation. All 53 patients had an insidious onset and gradual progression of behavioral changes. Nearly 70% had early withdrawal from usual activities and decreased initiative consistent with impaired regulation of personal conduct;7 these patients developed passivity, inertia, and inactivity. However, a decline in appropriate social interpersonal behavior was not initially manifest in the majority of FTD patients; tactless behavior or verbal outbursts characterized 40% on presentation. Loss of insight commonly accompanied the decreased initiative, but frank emotional blunting was less common.

Supportive features, including compulsive-like acts and speech changes, were frequent on presentation. There were prominent early stereotypies or compulsive-like behaviors; the most frequent were repetitive checking activities or trips to the bathroom (without other documented cause). The speech and language changes were primarily economy of utterances, where the patient did not initiate conversation or output was limited to short phrases.7 Responses to questions involved single-word replies or short phrases. Only 2 FTD patients had clear stereotypy of speech, echolalia, or perseverative speech on initial presentation.

On 2-year follow-up, 44 (83%) of the patients had all core criteria and many of the supportive features for FTD. In addition, about 20% developed hyperorality and dietary changes, consistent with the Klüver-Bucy syndrome (KBS). These patients had a tendency to explore their environment with their hands, also consistent with the KBS. None of these patients had hypersexuality, although they were generally disinhibited in sexual and other commentary. On follow-up, 1 patient had utilization behavior and 4 had grasp, snout, or sucking reflexes.

DISCUSSION

This study evaluated the Consensus Criteria among FTD patients who were initially diagnosed by using Lund and Manchester criteria and functional neuroimaging. Although the Lund and Manchester criteria have been highly sensitive and specific when applied by experienced clinicians,10 these criteria lacked sufficient precision. They included concepts such as early loss of social awareness and of personal awareness and did not specify the required number of core features (three) for the diagnosis of FTD.3 The Consensus Criteria appeared to resolve these issues.7 This study, however, found that only one-third of our FTD patients had all the necessary core features of the Consensus Criteria on initial presentation. The majority of the FTD patients had an early decline in behavioral initiative and insight, but more than half retained social interpersonal conduct and emotional expression until later in their course.

During life, FTD is commonly confused with Alzheimer's disease (AD), but these dementias are distinguishable by clinical features and functional neuroimaging.2,11 Unlike AD, FTD is usually a presenile disorder with an average age at onset of around 57 years and a usual range of 51 to 63 years.1,2 FTD, as opposed to AD, more often results in early social incorrectness, disinhibited behavior, loss of personal regulation, self-neglect, compulsive-like behavior, hyperorality, and a progressive reduction in verbal output.2,5,12–18 On cognitive measures, FTD patients differ from typical AD patients in manifesting early declines in executive functions in the face of relatively preserved memory and visuospatial abilities.2,5,12–16 The FTD patients in this study, like others in the literature, have a mild-to-moderate memory retrieval deficit on presentation. Functional imaging also distinguishes FTD from AD. In FTD, SPECT and PET scans show evidence of hypometabolism in frontal and anterior temporal regions compared with temporoparietal areas in AD.19,20 The neuroimaging changes of FTD are often initially asymmetric and worsen over time.6,21

FTD patients usually present with noncognitive neuropsychiatric symptoms that suggest a common underlying qualitative or quantitative loss of self-control.1 In the literature, the most commonly reported early symptom is worsened social interpersonal behavior.7,22 This includes declines in tactfulness and manners, violation of interpersonal space, inappropriate touching, and overt sexual behavior or exposure. FTD patients may become impulsive and verbally and physically disinhibited,23 and some of these patients have aggressive verbal outbursts or assaultive behavior.2,24 In addition, FTD patients neglect or lose interest in personal hygiene and fail to wash, bathe, groom, or dress appropriately.7 They may present unkempt and partially clothed, or they may urinate or defecate in front of others. Our results, however, suggest that FTD patients are more likely to become inactive early in the course, with decreased initiation of purposeful behavior, rather than to exhibit early frank social impropriety or disinhibition.22,25,26 Furthermore, family members often believe that the early personality changes, with inactivity and aspontaneity, represent a form of depression.

FTD patients often manifest emotional blunting, which must also be distinguished from depression. Their emotional blunting overlaps with the other personality changes and produces indifference and apathy rather than sadness or anhedonia. There is a lack of sympathy, empathy, emotional warmth, feelings of embarrassment, or awareness of the needs of others. The expression and perception of emotions, particularly anger and sadness, or of situations depicting a “social dilemma,” are deficient in FTD.27,28

There are other behavioral changes consistent with a “frontal lobe personality” syndrome. These include functional and work capacity due to problems with planning, organization, feedback correction, task completion, and mental flexibility. Abnormal frontal-executive behavior is further reflected in patients' decreased insight and awareness of their disability or the consequences of their behavior. Their corresponding judgment is abnormal, and FTD patients tend to give concrete answers on proverb interpretation. On neuropsychological tests, there is an early compromise of frontal-executive functions and the absence of severe amnesia, aphasia, or perceptuospatial disorder.13,14 Tests sensitive to ventromedial prefrontal orbitofrontal function show increased risk-taking, increased deliberation times on decision-making, and decreased visual discrimination learning.29 Although not common among our patients, other frontal behavioral changes may occur in FTD patients, including imitation and utilization behavior or frontal release signs such as grasp or other primitive reflexes.30

In our FTD patients, compulsive-like behaviors were common presenting symptoms.24,30 Perseverative and stereotyped behaviors encompass simple repetitive acts and verbal or motor stereotypies such as lip smacking, hand rubbing or clapping, counting aloud, and humming. They also encompass complex repetitive motor routines such as wandering a fixed route, collecting and hoarding objects, counting money, and rituals involving unusual toileting behavior.23,31,32 Some FTD patients have compulsive self-injurious behaviors such as trichotillomania and picking at fingers to the point of excoriation.33 These compulsive-like acts are not linked to intrusive thoughts or to overt anxiety as in obsessive-compulsive disorder.

As the disease progresses, most FTD patients appear to develop all five of the core symptoms of FTD, and many have elements of the KBS.2,34 There may be a rapid rate of progression in the first few years after diagnosis. The KBS, which results from bilateral damage to anterior temporal lobes and amygdalae, consists of passivity with loss of affective responses such as fear; oral exploratory behavior and altered dietary preferences; hypermetamorphosis (mandatory exploration of environment); sensory agnosia; and increased sexual activity. The most common symptom of the KBS in FTD is hyperorality manifested as cramming and bingeing, altered food preferences especially for sweets, food fads, weight gain, or increased smoking.17,34

Another common neuropsychiatric manifestation of FTD is a progressively decreased verbal output.32 Some FTD patients have predominant left hemisphere involvement and present with primary progressive aphasia (PPA) years before other manifestations.35 Even in the absence of PPA, however, FTD patients usually have decreased speech output and conversation with an economy of utterances (single-word or short phrases). Later, FTD patients can manifest reiterative speech such as stuttering, logoclonia, echolalia, palilalia, and verbal stereotypy, and language changes such as semantic anomia. Eventually, the development of mutism masks any residual underlying language ability.

Other neuropsychiatric symptoms are infrequent in FTD. Psychotic symptoms such as delusions and hallucinations are surprisingly rare and were absent in our 53 patients. Nevertheless, there have been reports of patients with an initial schizophrenia-like psychosis or a psychotic affective disorder as a prelude to FTD or to biopsy-proven FTD-Pick's.36,37 The presence of an affective psychosis may precede the development of FTD by many years.38 Occasionally FTD is associated with concurrent emotional disturbances—especially depression, but also mania with pressured speech, lability, anger, and irritability.2

Our retrospective assessment of the Consensus Criteria for FTD has several potential limitations. First, the original diagnosis depended on the Lund and Manchester criteria accompanied by functional neuroimaging. A full assessment of the value of clinical criteria for FTD depends on the presence of neuropathological confirmation. Second, the two sets of clinical criteria for FTD, for the most part, attempt to cover similar symptoms, and both sets of criteria provide a great deal of leeway for the interpretation of individual patient behaviors. Third, the clinicians could not be blinded to the original diagnosis in this retrospective study. Finally, judgments had to be made about the presence or absence of emotional blunting. Despite these limitations, this report illustrates the pattern of development of specific behaviors in FTD.

Consensus Criteria for FTD offer guidelines for diagnosis, but further refinement is needed, particularly for patients who lack early changes in social interpersonal conduct. On presentation, core diagnostic features are frequently absent and several supportive features may be more common. Further work is needed to validate the Consensus Criteria and to distinguish behaviors such as decreased initiative and verbal output from depression. Of particular value would be the repeat evaluation of Consensus Criteria on a yearly basis, along with concomitant functional neuroimaging.

FIGURE 1. Representative single-photon emission tomography scan of a patient with frontotemporal dementia, showing predominant frontotemporal hypometabolism.

|

|

|

1 Pasquier F, Lebert F, Lavenu I, et al: Diagnostic clinique des démences fronto-temporales. Rev Neurol 1998; 154:217-223Medline, Google Scholar

2 Mendez MF, Selwood A, Mastri AR, et al: Pick's disease versus Alzheimer's disease: a comparison of clinical characteristics. Neurology 1993; 43:289-292Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3 The Lund and Manchester groups: Clinical and neuropathological criteria for frontotemporal dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1994; 57:416-418Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4 Robert PH, Lafont V, Snowden JS, et al: Critères diagnostiques des dégénerescences lobaires fronto-temporales. Encephale 1999; 25:612-621Medline, Google Scholar

5 Lindau M, Almkvist O, Kushi J, et al: First symptoms: frontotemporal dementia versus Alzheimer's disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2000; 11:286-293Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6 Sjogren M, Gustafson L, Wikkelso C, et al: Frontotemporal dementia can be distinguished from Alzheimer's disease and subcortical white matter dementia by an anterior-to-posterior rCBF-SPET ratio. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2000; 11:275-285Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7 Neary D, Snowden JS, Gustafson L, et al: Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: a consensus on clinical diagnostic criteria. Neurology 1998; 51:1546-1554Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8 Folstein W, Folstein SE, McHugh PR: “Mini-Mental State”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975; 12:189-198Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9 Hughes CP, Berg L, Danzinger WL, et al: A new clinical scale for the staging of dementia. Br J Psychiatry 1982; 140:566-572Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10 Lopez OL, Litvan I, Catt KE, et al: Accuracy of four clinical diagnostic criteria for the diagnosis of neurodegenerative dementias. Neurology 1999; 53:1292-1299Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11 Varma AR, Snowden JS, Lloyd JJ, et al: Evaluation of the NINCDS-ADRDA criteria in the differentiation of Alzheimer's disease and frontotemporal dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1999; 66:184-188Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12 Bozeat S, Gregory CA, Ralph MA, et al: Which neuropsychiatric and behavioural features distinguish frontal and temporal variants of frontotemporal dementia from Alzheimer's disease? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2000; 69:178-186Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13 Mendez MF, Cherrier M, Perryman KM, et al: Frontotemporal dementia versus Alzheimer's disease: differential cognitive features. Neurology 1996; 47:1189-1194Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14 Pachana NA, Boone KB, Miller BL, et al: Comparison of neuropsychological functioning in Alzheimer's disease and frontotemporal dementia. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 1996; 2:505-510Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15 Miller BL, Ikonte C, Ponton M, et al: A study of the Lund-Manchester research criteria for frontotemporal dementia: clinical and single-photon emission CT correlations. Neurology 1997; 48:937-942Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16 Rozzini L, Lussignoli G, Padovani A, et al: Alzheimer disease and frontotemporal dementia (letter). Arch Neurol 1997; 54:350Google Scholar

17 Miller BL, Darby AL, Swartz JR, et al: Dietary changes, compulsions and sexual behavior in frontotemporal degeneration. Dementia 1995; 6:195-199Medline, Google Scholar

18 Neary D, Snowden JS: Fronto-temporal dementia: nosology, neuropsychology, and neuropathology. Brain Cogn 1996; 31:176-187Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19 Alexander CE, Prohovnik I, Sackeim HA, et al: Cortical perfusion and gray matter weight in frontal lobe dementia. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1995; 7:188-196Link, Google Scholar

20 Miller BL, Cummings JL, Villanueva-Meyer J, et al: Frontal lobe degeneration: clinical, neuropsychological, and SPECT characteristics. Neurology 1991; 41:1374-1382Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21 Miller BL, Gearhart R: Neuroimaging in the diagnosis of frontotemporal dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 1999; 10(suppl 1):71-74Google Scholar

22 Galante E, Muggia S, Spinnler H, et al: Degenerative dementia of the frontal type: clinical evidence from 9 cases. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 1999; 10:28-39Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23 Hooten WM, Lyketsos CG: Frontotemporal dementia: a clinicopathological review of four postmortem studies. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1996; 8:10-19Link, Google Scholar

24 Mendez MF, Perryman KM, Miller BL, et al: Compulsive behaviors as presenting symptoms of frontotemporal dementia. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 1997; 10:154-157Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25 Levy ML, Miller BL, Cumming JL, et al: Alzheimer disease and frontotemporal dementias. Behavioral distinctions. Arch Neurol 1996; 53:687-690Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26 Kertesz A, Nadkarni N, Davidson W, et al: The Frontal Behavioral Inventory in the differential diagnosis of frontotemporal dementia. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2000; 6:466-468Google Scholar

27 Gregory CA, Orrell M, Sahakian B, et al: Can frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer's disease be differentiated using a brief battery of tests? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1997; 12:375-383Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28 Lavenu I, Pasquier F, Lebert F, et al: Perception of emotion in frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 1999; 13:96-101Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29 Rahman S, Sahakian BJ, Hodges JR, et al: Specific cognitive deficits in mild frontal variant frontotemporal dementia. Brain 1999; 122:1469-1493Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30 Shimomura T, Mori E: Obstinate imitation behaviour in differentiation of frontotemporal dementia from Alzheimer's disease. Lancet 1998; 352:623-624Google Scholar

31 Tonkonogy JM, Smith TW, Barreira PJ: Obsessive-compulsive disorders in Pick's disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1994; 6:176-180Link, Google Scholar

32 Snowden JS, Neary D, Mann DM, et al: Progressive language disorder due to lobar atrophy. Ann Neurol 1992; 31:174-183Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33 Mendez MF, Bagart B, Edwards-Lee T: Self-injurious behavior in frontotemporal dementia. Neurocase 1997; 3:231-236Crossref, Google Scholar

34 Mendez MF, Foti DJ: Lethal hyperoral behavior from the Klüver-Bucy syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1997; 62:293-294Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35 Kertesz A, Hudson L, Mackenzie IR, et al: The pathology and nosology of primary progressive aphasia. Neurology 1994; 44:2065-2072Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36 Lamote H, Tan KL, Verhoeven WM: Frontotemporale dementie bij een jonge vrouw met ogenschijnlijk schizofrenie. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 1998; 142:2698-2699Google Scholar

37 Waddington JL, Youssef HA, Farrell MA, et al: Initial “schizophrenia-like” psychosis in Pick's disease: case study with neuroimaging and neuropathology, and implications for frontotemporal dysfunction in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 1995; 18:79-82Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38 Mendez M, Lipton A: Emergent neuroleptic hypersensitivity as a herald of presenile dementia. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2001; 13:347-356Link, Google Scholar