Olfactory Dysfunction Discriminates Alzheimer's Dementia From Major Depression

Abstract

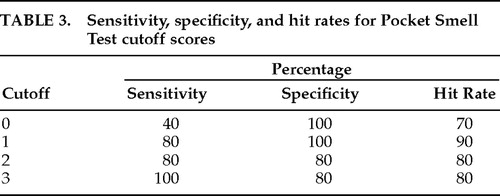

This study tested the hypothesis that olfactory dysfunction could discriminate between groups of patients with Alzheimer's disease and major depression. Forty patients meeting DSM-IV criteria for Alzheimer's disease and for major depression (20 per group) underwent assessment with the Pocket Smell Test (PST), a three-item screening measure of cranial nerve I function. A PST score of ≤1 (1 or 0 correct) discriminated between the groups with a hit rate of 90% (sensitivity=80%, specificity=100%). Olfactory assessment may be a useful adjunctive screening measure in differentiating Alzheimer's disease from depression in elderly patients.

The differential diagnosis of neurodegenerative dementia from primary psychiatric illness (major affective disorders in particular) can be, in some cases, a challenging task for neuropsychiatrists and neuropsychologists who evaluate and treat elderly patients. An impressive armamentarium of neurodiagnostic techniques (including MRI, PET, SPECT, and neuropsychological testing) exists to assist in this process, and each approach has its strengths and limitations. Historically, most clinicians have relied on a combination of diagnostic techniques for differentiating Alzheimer's from depression (keeping in mind, of course, that these are not mutually exclusive clinical entities). In some instances, particular neurodiagnostic methods are unavailable or test results are equivocal. Inaccurate diagnosis may lead to dramatic treatment consequences. Recently, neuroscientists have sought to identify more cost-effective, time-effective, and user-friendly strategies that have adequate sensitivity, specificity, and hit rates to address this diagnostic issue. Olfactory assessment has emerged as a novel approach.

Doty1 summarized studies documenting loss of olfactory discrimination in Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, progressive supranuclear palsy, and Huntington's disease and cited research attesting to diminished olfactory acuity in normal aging, schizophrenia, and vascular dementia. In particular, he reviewed 13 studies investigating olfaction in Alzheimer's patients relative to age-matched control subjects and concluded that the vast majority of studies found significantly decreased function in Alzheimer's patients. Nordin and Murphy2 documented impaired olfaction in patients with questionable Alzheimer's versus age-matched control subjects. Morgan et al.3 reported that odor identification tasks could be useful in diagnosing Alzheimer's and that the lexical impairments of Alzheimer's were not responsible for the smell identification deficit. A postmortem neuropathological study4 has demonstrated increased numbers of neurofibrillary tangles and neuritic plaques in the olfactory cortex of Alzheimer's patients versus age-matched control subjects. Doty1 has suggested that the magnitude of the olfactory deficit parallels the progression and severity of the Alzheimer's process.

There is no empirical evidence to indicate (or theoretical rationale to suspect) that olfactory deficits are associated with depression in the elderly. It has been previously hypothesized5 that olfactory dysfunction could discriminate patients with Alzheimer's from those with depression, since there is no reason to believe that patients with depression would perform any differently on olfactory tests than the age-matched control subjects used in the prior Alzheimer's studies reported in the literature. A pilot clinical study explored this hypothesis,5 and the results indicated that performance on a standardized test of olfaction discriminated between 29 Alzheimer's patients and 10 age-matched depressed patients at a statistically significant level and with a hit rate of 87.18%. However, the pilot study contained several methodological flaws. The present study was designed to test this hypothesis adequately with improved experimental design and methodology.

METHODS

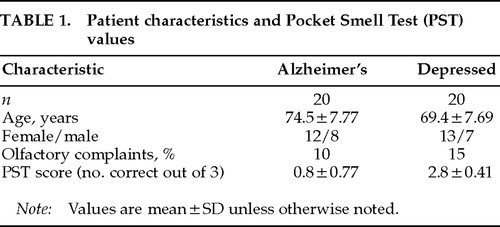

Patients in this study were at least 55 years old, met DSM-IV6 criteria for the diagnosis of Alzheimer's dementia or major depression, and gave informed consent. Diagnoses had been established by board-certified (adult and/or geriatric) psychiatrists who had the opportunity to follow these patients for extended longitudinal observation. Patients were excluded if they had a history of neurologic disorder that could affect olfaction adversely (such as traumatic brain injury). Demographic characteristics of the patient groups are presented in Table 1.

All patients underwent olfactory assessment with the Pocket Smell Test (PST),7 a three-item microencapsulated “scratch and sniff” measure derived from the University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test.8 The PST has been shown to be sensitive to olfactory deficits in Alzheimer's.9 Prior to PST administration, each patient was queried as to whether he or she had noted any recent change in sense of smell (see Table 1). The PST was then administered by the authors under standardized instructions. Each of the three PST tasks contains four response alternatives. (Target odors included smoke, lilac, and lemon.) After releasing the odor, the examiner read the four response alternatives continuously until the patient responded. Patients were encouraged to guess if they were unsure. Nostrils were not tested separately.10

RESULTS

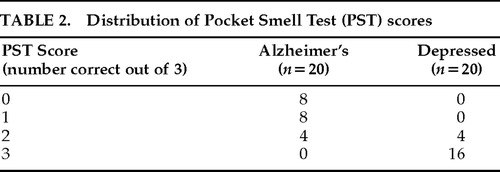

The distribution of PST scores is presented in Table 2. The Alzheimer's group, which was slightly older than the depressed group (P=0.044), performed significantly worse than the depressed group on the PST (t=10.274, df=38, P<0.0001). Table 3 lists sensitivity, specificity, and hit rate data for various cutoff scores on the PST. A cutoff score of 1 (indicating a score of 0 or 1 correct on the PST, or 2 or more errors) yielded optimal classification; there were four false negatives in the Alzheimer's group and no false positives. Two of the Alzheimer's patients (10%) and 3 of the depressed patients (15%) reported awareness of olfactory decline.

DISCUSSION

The results of this small, nonblind study support the hypothesis that olfactory assessment can assist in differentiating Alzheimer's from depression in the elderly. In the context of a methodologically improved design, these results are consistent with the findings noted in the pilot study.5 Despite the reliability of these findings, we are inclined to view these results as preliminary, and we would encourage replication in other settings with more rigorous experimental methodology (for example, using larger samples where experimenters are blind to hypothesis and patient group assignment).

The Alzheimer's group was slightly older than the depressed group, and this mild disparity could be of significance given the age-related decline in olfactory acuity.11 Correlations between age and PST performance were virtually nil for the depressed group (r=0.04) and weak for the Alzheimer's group (r=–0.23). Age accounted for virtually no variance in PST performance in the depressed group and only about 5% of the variance in the Alzheimer's group, thus diminishing the significance of the group age difference. Nonetheless, future studies should endeavor to have groups with no age differences.

Clinically, it was noteworthy that no patient spontaneously complained of olfactory decline and that even upon direct questioning, 90% of the Alzheimer's patients and 85% of the depressed patients reported no olfactory changes. These results are consistent with the findings of Nordin et al.,12 who found that 74% of Alzheimer's patients and 77% of their normal elderly control subjects (with objective evidence of smell loss) reported normal smell sensitivity. Patient report of olfactory dysfunction thus appears to be an unreliable indicator, and formal testing is warranted.

The specificity index of 100% for Alzheimer's is truly encouraging; however, the 4 patients with false negative findings are problematic. Retrospective study of these 4 reveals that all were relatively young (mean age 70.5 years) and were probably in the early stages of Alzheimer's (mild level of impairment). A weakness of this study was the lack of cognitive measures; it would be useful in future studies to include severity ratings for Alzheimer's and depression along with the Mini-Mental State Examination or other cognitive measures so that olfactory scores could be correlated with degree of neurobehavioral impairment. In this way Doty's1 hypothesis of progressive olfactory decline as a function of disease severity could be better assessed.

Use of olfactory assessment to assist in the differential diagnosis of Alzheimer's versus depression has several advantages. The PST is easy to administer, time- and cost-efficient (it takes about 2 minutes and costs about $1.50), and well tolerated by patients. (No one refused the test.) It is also not greatly affected by education or literacy levels, variables with confounding potential on many standard neuropsychological tests. PST findings also have practical implications for patient safety and perhaps for appropriate treatment.

A weakness of this approach is that olfactory assessment is not an adequate substitute for a thorough neuropsychiatric and neuropsychological evaluation. Further, these findings are limited in that all patients in this study diagnosed with Alzheimer's actually are cases of probable Alzheimer's disease; autopsy would be required for confirmation. Any misdiagnoses could certainly alter these results. Additionally, it should be emphasized that poor PST performance may indicate Alzheimer's but does not rule out comorbid depression. We view olfactory testing as a potentially useful adjunctive technique; its ultimate diagnostic value remains to be cross-validated empirically in future research. In the meantime, we encourage clinicians to use olfactory assessment in their evaluation of elderly patients who pose a diagnostic challenge, since this approach appears to hold promise.

|

|

|

1. Doty RL: Olfactory dysfunction in neurodegenerative disorders, in Smell and Taste in Health and Disease, edited by Getchell TV. New York, Raven, 1991, pp 735–751Google Scholar

2. Nordin S, Murphy C: Impaired sensory and cognitive olfactory function in questionable Alzheimer's disease. Neuropsychology 1996; 10:113–119Crossref, Google Scholar

3. Morgan CD, Nordin S, Murphy C: Odor identification as an early marker for Alzheimer's disease: impact of lexical functioning and detection sensitivity. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 1995; 17:793–803Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Reyes PF, Deems DA, Suarez MG: Olfactory-related changes in Alzheimer's disease: a quantitative neuropathological study. Brain Research Bulletin 1993; 32:1–5Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Solomon GS: Does olfactory dysfunction discriminate Alzheimer's disease from major depression? A preliminary clinical study. Paper presented at the Tennessee Psychological Association convention, Gatlinburg, TN, October 1996Google Scholar

6. American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

7. Sensonics, Inc.: The Pocket Smell Test. Haddon Heights, NJ, Sensonics, Inc., n.d.Google Scholar

8. Doty RL, Shaman P, Dann M: Development of the University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test: a standardized microencapsulated test of olfactory function. Physiol Behav 1984; 32:489–502Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Solomon GS: Anosmia in Alzheimer's disease. Percept Mot Skills 1994; 79:1249–1250Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Bromley SM, Doty RL: Odor recognition memory is better under bilateral than unilateral test conditions. Cortex 1995; 31:25–40Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Doty R: The Smell Identification Test Administration Manual. Haddonfield, NJ, Sensonics, Inc., 1983Google Scholar

12. Nordin S, Monsch AU, Murphy C: Unawareness of smell loss in normal aging and Alzheimer's disease: discrepancy between self-reported and diagnosed smell sensitivity. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 1995; 50B:187–192Google Scholar