Steroid-Responsive Charles Bonnet Syndrome in Temporal Arteritis

Abstract

The authors report a patient with biopsy-proven temporal arteritis who manifested Charles Bonnet syndrome (CBS). Treatment with steroid resulted in prompt resolution of visual hallucinations, despite persistent visual loss, suggesting that cerebral ischemia is a cofactor for the development of CBS.

Hallucinations are perceptual experiences in the absence of external sensory stimuli and occur most commonly with altered mental status due to toxic metabolic states, dementia, or psychiatric disorders.1,2 However, isolated visual hallucinations can occur in psychologically normal individuals who have visual loss due to lesions in peripheral or central visual pathways.1–11 This condition referred to as Charles Bonnet syndrome (CBS) has been attributed to “cortical release” phenomena due to lack of visual input.1–11

Advanced age is a risk factor for the development of CBS, yet the majority of older individuals with visual loss do not develop visual hallucinations, raising questions about the nature of this “age-related” risk factor.3–11 We studied the anatomical and behavioral substrates of CBS in a 79-year-old woman with biopsy-proven temporal arteritis.

CASE REPORT

Clinical Presentation

A 79-year-old right-handed woman awoke with sudden loss of peripheral vision and reported, “I can only see straight ahead.” Over the next few days she reported seeing images of flashing lights, flying bugs, birds, dogs, and humans within the area of visual loss. These images occurred daily, lasted for hours, contained color, and disappeared when she looked at them. She knew they were unreal and was not frightened. She had no loss of consciousness; mental status impairment; convulsions; language, motor, or sensory deficits; jaw claudication; scalp tenderness; headache; or fever. She had had three brief episodes of paresthesia and dysarthria 2 years earlier and, subsequently, took warfarin for presumed vertebrobasilar ischemia. She had no history of trauma, ocular, or psychiatric disease. She was alert, oriented, and provided a detailed history. Vital signs were within normal limits. General medical and neurological examinations were normal except for visual loss.

Neuro-Ophthalmological Examination

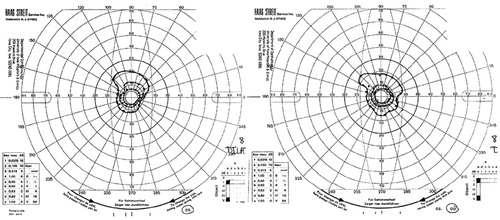

Goldman perimetry showed bilateral concentric reduction of the visual fields, leaving an area of preserved vision around fixation (keyhole vision) (Figure 1). Corrected visual acuity was 20/30 OU. Pupils were 5 mm OU and constricted to 3 mm to light. Fundi were normal. The cup/disc ratio was 0.3 in each eye. Critical flicker fusion was 32.5/30.8. Stereoacuity was 40 seconds of arc on the Titmus Test. Worth Four Dot Test showed fusion at near and distance. Ocular motility was full. Saccades were normal, and there was no nystagmus. Slit lamp examination showed mild cataract. Intraocular pressure by applanation tonometry was normal (16 mmHg OD, 17 mmHg OS). Electroretinogram was also normal.

MRI

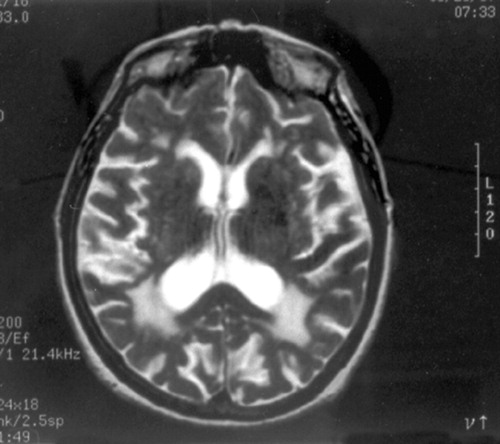

Brain MRI showed extensive confluent lesions affecting the optic radiation in the periventricular white matter of the occipital lobes (Figure 2).

EEG

Electroencephalogram showed delta-theta slow waves in the posterior regions and no epileptiform activity.

Neuropsychological Assessment

Neuropsychological assessment showed average intellectual skills, consistent with educational and occupational background. The patient was alert and fully oriented. Her speech was logical and goal-directed, not circumstantial or tangential. Affect was broad and appropriate to content and mood was euthymic. The patient’s conversational speech was fluent and articulate without paraphasia or dysprody, and speech comprehension was normal. She performed within normal limits on tests of anterograde verbal memory, delayed verbal recall and recognition, retrograde/remote memory, speeded visual information processing, rapid cognitive shifting, and working memory. She did not have visual object agnosia, prosopagnosia, simultanagnosia, ocular apraxia, or optic ataxia. However, she did show mild weaknesses in associative verbal fluency, visuoconstruction, and delayed visual memory. These findings did not show psychiatric disease or dementia.

Laboratory Tests

Serum chemistry, complete blood count, antinuclear antibody, cerebrospinal fluid, carotid Doppler, chest X-ray, electrocardiogram, and transthoracic echocardiogram were all normal. International normalized ratio was elevated at 2.4. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein were elevated at 102 mm/hour (normal values=0–20) and 6.2 mg/dl (normal values=0–0.5), respectively.

Biopsy

Temporal artery biopsy showed transmural inflammation with numerous giant cells, a reactive thickening of the intima with concomitant compromise of the vascular lumen, which is consistent with active giant-cell arteritis.

Treatment and Clinical Course

The patient’s visual hallucinations, which she experienced daily for 3 months, resolved completely within 1 week of treatment with oral prednisone 80 mg/day, yet the neuro-ophthalmologic examination, including her visual fields, remained unchanged. After 2 months of prednisone therapy, her ESR was 7, and her CRP was 0.7. Her visual fields were still constricted, and she remained free of hallucinations.

DISCUSSION

Our patient had visual hallucinations, visual loss, and biopsy-proven temporal arteritis. Treatment of temporal arteritis resulted in resolution of the visual hallucinations, despite persistent visual loss.

Visual loss is the most widely recognized neuro-ophthalmological complication of temporal arteritis.12 It can be caused by ischemia of retina, choroid, optic nerve, optic chiasm, optic tract, optic radiation, and, rarely, occipital cortex.12 In our patient, the normal funduscopic examination and electroretinogram argued against ischemic optic neuropathy, central artery branch occlusion, or choroidal ischemia. The pattern of her visual loss (i.e., keyhole vision) was suggestive of a lesion in the retrochiasmatic visual pathways.13 Indeed, her brain MRI demonstrated such lesions, affecting the optic radiation in the periventricular white matter of the occipital lobes.

Our patient’s visual hallucinations were confined to the defective visual field, variable in content, were prolonged in duration, were influenced by eye movements, and were not associated with dementia, psychiatric disorder, or epileptiform activity on EEG. Thus, she met the criteria for CBS.1–11

A gradual spontaneous resolution of visual hallucinations has been reported in patients with CBS.3,4,9,11 However, the rapid and complete resolution of our patient’s chronic daily visual hallucinations in response to steroid treatment indicated the effective treatment of temporal arteritis. The prompt resolution of visual hallucinations with steroid treatment occurred, despite persistent visual loss, implying that the visual loss, was not sufficient to account for the patient’s visual hallucinations. While a direct effect of steroid on neuronal metabolism and, therefore, on visual hallucinations remains conceivable, we suggest that the second causative and necessary steroid-responsive factor was posterior circulation ischemia due to temporal arteritis.12–18 Posterior circulation ischemia could also explain the patient’s previous transient episodes of paresthesia and dysarthria and her findings on MRI (the extensive lesions in the periventricular white matter of the occipital lobes), EEG (the abnormal slowing in the posterior regions), and the neuropsychological tests (the selective deficits on visual memory). In contrast to previous reports of CBS in temporal arteritis (only nine cases described in the literature), where the visual hallucinations were attributed to either posterior circulation ischemia or “cortical release” due to visual loss,14–17 the unique feature in our patient was that both mechanisms were necessary but dissociable with steroid treatment. Indeed, both mechanisms have been recently reported to cause cortical hyperexcitability, which is thought to be the physiological substrate of visual hallucinations in CBS.5–11,19

Visual loss and advanced age are the two well-known risk factors for the development of CBS.3–11 However, the majority of older individuals with visual loss do not develop CBS. While the mechanism by which visual loss contributes to development of CBS is thought to be “cortical release and hyperexcitability” due to lack of visual input,1–11 the nature of the “age-related” risk factor is still unknown. This report suggests that cerebral ischemia (possibly through resulting cortical hyperexcitability) is the “age-related” risk factor for the development of CBS. Along these lines, patients with CBS have greater incidence of posterior cerebral hypoperfusion and periventricular white matter lesions than healthy comparison subjects.20,21 Thus, investigation of CBS should include both ocular and cerebrovascular causes, including temporal arteritis.

While most patients with CBS require only education and reassurance, symptomatic treatments, including nonpharmacologic interventions such as improving the surrounding lighting, or pharmacological interventions with anticonvulsants or atypical antipsychotics, are available.9,10,22 However, recent reports of successful treatment22 such as removal of the cataract, laser photocoagulation of retinal hemorrhage, or (as demonstrated in this report) steroid treatment of temporal arteritis indicate that the more direct and effective approach for managing patients with CBS is to treat the underlying disease.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. A. Shirani, Department of Psychiatry, and Drs. P. Opal, C.O. Martin, and H.P. Adams, Department of Neurology, University of Iowa, for their helpful comments.

FIGURE 1. Goldman Perimetry Shows bilateral Concentric Reduction of the Visual Fields, Leaving an Area of Preserved Vision Around Fixation (Keyhole Vision)

FIGURE 2. T2-weighted MRI of the Brain Shows Extensive Confluent Lesions Affecting the Optic Radiation in the Periventricular White Matter of the Occipital Lobes

MRI=magnetic resonance imaging

1 Cummings JL, Miller BL: Visual Hallucinations: clinical occurrence and use in differential diagnosis. West J Med 1987; 146:46–51Medline, Google Scholar

2 Rizzo M, Barton JJS: Positive visual phenomena, in Walsh and Hoyt’s Clinical Neuro-Ophthalmology, vol 1. Edited by Miller NR, Newman NJ. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1998, pp 454–467Google Scholar

3 Teunisse RJ, Cruysberg JR, Hoefnagels WH, et al.: Visual hallucinations in psychologically normal people: Charles Bonnet’s syndrome. Lancet 1996; 347:794–797Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4 Fernandez A, Lichtshein G, Vieweg WVR: The Charles Bonnet syndrome: a Review. J Nerv Ment Dis 1997; 185:195–200Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5 Manford M, Andermann F: Complex visual hallucinations: clinical and neurobiological insights. Brain 1998; 121:1819–1840Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6 ffytche DH, Howard RJ, Brammer MJ, et al.: The anatomy of conscious vision: an fMRI study of visual hallucinations. Nat Neurosci 1998; 1:738–742Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7 ffytche DH, Howard RJ: The perceptual consequences of visual loss: “positive” pathologies of vision. Brain 1999; 122:1247–1260Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8 Cole M: When the left brain is not right the right brain may be left: report of personal experience of occipital hemianopia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1999; 67:169–173Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9 Rovner BW: The Charles Bonnet syndrome: visual hallucinations caused by vision impairment. Geriatrics 2002; 57:45–46Medline, Google Scholar

10 Mewasingh LD, Kornreich C, Christiaens F, et al.: Pediatric phantom vision (Charles Bonnet) syndrome. Pediatr Neurol 2002; 26:143–145Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11 Burke W: The neural basis of Charles Bonnet hallucinations: a hypothesis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2002; 73:535–541Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12 Caselli RJ, Hunder GG: Giant cell (temporal) arteritis. Neurol Clin 1997; 15:893–902Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13 Bender MB, Rudolph SH, Stacy CB: The neurology of the visual and oculomotor system, in Clinical Neurology, vol 1. Edited by Joint RJ. Philadelphia, Lippicott-Raven, 1997, pp 32–42Google Scholar

14 Hart TC: Formed visual hallucinations: a symptom of cranial arteritis. Br Med J 1967; 3:643–644Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15 Simeon-Aznar CP, Fonolosa-Pla V, Cuenca-Luque R, et al.: [Visual hallucinations in Horton’s arteritis (letter).] Med Clin (Barc) 1990; 94:398 (Spanish}Medline, Google Scholar

16 Sonnenblick M, Nesher R, Rozenman Y, et al: Charles Bonnet syndrome in temporal arteritis. J Rheumatol 1995; 22:1596–1597Medline, Google Scholar

17 Nesher G, Nesher R, Rozenman Y, et al.: Visual hallucinations in giant cell arteritis: association with visual loss. J Rheumatol 2001; 28:2046–2048Medline, Google Scholar

18 Johnson H, Bouman W, Pinner G: Psychiatric aspects of temporal arteritis: a case report and review of the literature. Psychiatry Neurol 1997; 10:142–145Google Scholar

19 Wunderlich G, Suchan B, Volkmann J, et al.: Visual hallucinations in recovery from cortical blindness. Arch Neurol 2000; 57:561–565Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20 Shedlack KJ, McDonal WM, Laskowitz DT, et al.: Geniculocalcarine hyperintensities on brain magnetic resonance imaging associated with visual hallucinations in the elderly. Psychiatry Res 1994; 54:283–293Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21 Adachi N, Nagayama M, Anami K, et al.: Asymmetrical blood flow in the temporal lobe in the Charles Bonnet Syndrome: serial neuroimaging study. Behav Neurol 1994; 7:97–99Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22 Batra A, Bartels M, Wormstall H, et al.: Therapeutic options in Charles Bonnet syndrome. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1997; 96:129–133Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar