Prevalence of Apathy, Dysphoria, and Depression in Relation to Dementia Severity in Alzheimer’s Disease

Abstract

Apathy is common in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) but may be confused with depression due to overlap in symptoms queried in depression assessments. Depression and dysphoria appear to occur less frequently in AD but are better researched. This study examined the relative frequency of these syndromes and their relation to disease characteristics in 131 research participants with probable or possible AD. Apathy was more prevalent than dysphoria or major depression and was more strongly associated with global disease severity, cognitive impairment, and functional deficits. Accurate differential diagnosis of apathy and depression is key to appropriate family education and effective treatment.

Apathy is broadly defined as a loss of motivation and manifests in behaviors such as diminished initiation, poor persistence, lowered interest, indifference, low social engagement, blunted emotional response, and lack of insight.1 Apathy is a prominent and extremely common feature of the behavioral and personality changes in Alzheimer’s disease (AD),2–5 occurring in 61% to 92% of AD patients.2,3 Symptoms present early in the illness and persist through the disease course.2,3,6–8

In addition to its high prevalence, apathetic behavior in AD patients is an important factor in clinical management, as it places additional burden on caregivers already caring for patients with diminished abilities. Apathetic patients are more impaired in their ability to perform basic activities of daily living (ADL) than their cognitive status would suggest4,5 and rely on caregivers to initiate activities that they are capable of doing. Caregivers who lack an understanding of apathy as a part of AD may misinterpret the apathetic behavior as laziness, deliberate opposition, or lack of caring.9 Not surprisingly, caregivers of apathetic dementia patients report significant levels of distress.10,11

Depression in AD, although of lower prevalence, has received much more attention in the literature than apathy. Although a wide range of depression reported across studies (0%–87%),12,13 best estimates of the overall prevalence of comorbid clinically significant depression (usually diagnosed by DSM criteria) are approximately 20% in clinical samples of persons with probable or possible AD and 13% in community samples of persons with dementia.14–18 Depressive symptoms are more common in AD than major depression but still found to be less common than apathy. In a review of studies of affective symptoms in AD, the median frequency for depressed mood was 41%, with modal frequencies commonly between 40% and 50%.19 Similar findings were reported in a study using the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI),20 which reported that 38% of a sample of 50 AD patients had some dysphoria symptoms.2

Differentiating apathy from depression in dementia is difficult because of substantial overlap in key symptoms. According to DSM-IV,21 a principal symptom of depression may be loss of interest or pleasure in activities instead of depressed mood. However, in adults with dementia, loss of interest or pleasure in activities may reflect a loss of motivation or ability rather than depression or affective changes. Further complicating the diagnosis of depression in dementia is that the dementia process itself commonly produces vegetative symptoms, such as hypersomnia, fatigue, and weight loss.22 Since DSM criteria allow for the diagnosis of major depression without depressed mood, the high levels of apathy and vegetative symptoms in AD may be artifacts that increase the apparent prevalence of major depression in dementia.2

Instruments used in research may also confound the behavioral syndromes of apathy and dysphoria. Marin et al.23 noted that the overlap between apathy, assessed by the Apathy Evaluation Scale (AES),24 and depression, assessed by the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D),25 was due to items in the latter scale that assess symptoms more directly associated with dementia (such as diminished work/interest, psychomotor retardation, lack of energy, and loss of insight). Items assessing dysphoria (e.g., depressed mood, guilt, hopelessness) were, at best, weakly associated with apathy. The discrimination of apathy from depression in dementia is important because of growing evidence of distinct pathophysiology and differences in pharmacological and psychosocial interventions suitable for the two syndromes.1

Recent studies demonstrate that apathy and dysphoria can be clinically differentiated with carefully constructed instruments that exclude vegetative symptoms and discretely measure apathy and dysphoria.20,23,26 This study evaluated the prevalence of apathy, dysphoria, and major depression in a series of research subjects with AD and explored the differential relationship of these behavioral syndromes with other clinical aspects of AD in order to provide further support for the differentiation of apathy from mood disturbances. We hypothesized that apathy would be more prevalent than dysphoric behavior and more robustly correlated with disease severity measures.

METHOD

Participants

For this study we evaluated archival patient clinical information and behavioral symptom data on a total of 131 participants (61 men; 70 women) in the University Memory and Aging Center Research Registry of University Hospitals of Cleveland, Ohio. Our sample included all research registry participants with a diagnosis of probable (N=48) or possible AD (N=83) based on National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Diseases and Stroke/Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS-ADRDA) criteria27 using a consensus case conference method, and with complete behavioral symptoms data. Participants with a possible AD diagnosis either lacked some diagnostic testing specified in NINCDS-ADRDA criteria for probable AD or had other potential contributing causes to dementia.

Measures

Apathy.

Apathy was assessed using the Dementia Apathy Interview and Rating (DAIR),26 a 16-item structured interview with the primary caregiver designed to assess illness-related changes in motivation, emotional responsiveness, and engagement. Each interview question consists of two parts. First, the interviewer asks how often a specific behavior was observed over the past month. Second, caregivers are asked whether behavior questioned in the item had changed from the time prior to the memory loss. Items are counted in the final apathy score only if the behavior represents a change toward apathy from preillness behavior. For example, if a person almost never started conversations during the month queried, the item counts in the total apathy score only if initiation of conversation has decreased since illness onset but not if the level is comparable to preillness behavior. The apathy score is a sum of all items reflecting change, divided by the number of items completed, with higher scores representing greater average apathy. Apathy scores can range from 0 (patient shows apathetic behavior almost never or less than once a week) to 3 (patient shows apathetic behavior almost always or almost every day).

Dysphoria.

Dysphoric symptoms were assessed from caregiver informant reports with the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD) Behavior Rating Scale for Dementia (BRSD), which measures the frequency with which specific behaviors occurred within the prior month.22 Dysphoria scores were derived from the depression subscale of the BRSD. This subscale consists of seven items evaluating sad appearance, hopelessness, crying, guilt feeling, poor self-esteem, anxiety, and suicidal ideation. The dysphoria score is the sum of all items divided by the number of items administered, with higher scores representing greater average dysphoria. Dysphoria scores can range from 0 (no dysphoric behavior in past month) to 4 (dysphoric behavior seen on more than 15 days per month, or more than one-half the time).

Depression Syndrome.

Syndromic depression was assessed according to DSM-IV criteria21 by medical staff from an interview with the caregiver informant. Informants were asked if in the past year the patient has had a 2-week period in which specific depressive symptoms have been present. Symptoms queried were: felt sad, blue, depressed, empty or tearful; lost interest in things that used to be pleasurable; lost appetite; lost weight; had difficulty sleeping or slept too much; felt tired all the time; had to be moving all the time, or had difficulty getting going; felt worthless, sinful, or guilty; wanted to die or considered suicide. Subjects were classified as having major depression if five or more symptoms were present in the same 2-week period, and if one of the symptoms was sad mood or loss of interest.

Dementia Severity.

The cognitive and functional status of participants was evaluated with three measures: the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)28 to characterize severity of cognitive impairment, on which a higher score indicates better cognitive function; the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR)29 to characterize globally dementia stage, on which a higher score indicates greater dementia severity and lower overall function; and the Blessed Dementia Rating Scale (BDRS)30 to describe capacity to perform ADL, on which a higher score indicates greater impairment in daily living skills.

Procedure.

Caregiver informants completed apathy (DAIR) and behavioral symptom (BRSD) interviews with research assistants. All research assistants had extensive training and experience in conducting structured interviews and in working with patients with neurodegenerative diseases and their caregivers. Depression and adaptive living skills (BDRS) were assessed as a portion of an interview conducted with the caregiver informant by medical staff (doctor or nurse practitioner) to evaluate medical, mental, and functional status. Medical staff also completed a clinical and neurological examination of the patient to provide assessment of dementia severity (CDR).

Data Analysis

In order to test our hypothesis that apathy would be more prevalent than dysphoria or depression, we examined frequency distributions and mean scores. We dichotomized the apathy and dysphoria scores into high and low groups and used matched-pair t test for proportions to compare the percentage of patients with high apathy versus high dysphoria. To examine our prediction that apathy would be more robustly correlated with disease severity, Pearson correlation coefficients were used. We also explored whether apathy and dysphoria were associated with one another in two ways. We compared categorical variables (e.g., high/low apathy or high/low dysphoria) using phi (correlation coefficient for a 2×2 table). Since dichotomizing continuous variables may reduce their association, we also computed the rank-order correlation between untransformed apathy and dysphoria scores using Spearman’s rho. Two-tailed t tests were used to examine differences between groups, to evaluate skewness in distribution of apathy and dysphoria scores, and to examine the differences in the strength of associations between disease severity measures and apathy or dysphoria.

RESULTS

Characteristics of Participants

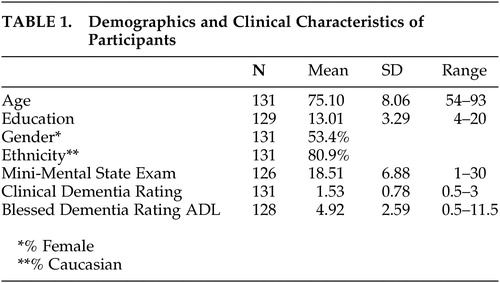

The clinical and demographic characteristics of the sample are summarized in Table 1. Participants ranged in age from 54 to 93, with an average age of 75 years (SD = 8.1). While participants were generally well-educated (mean = 13, SD = 3 years), there was a broad range in years of school completed (4–20 years).

The majority of participants in this study had dementia in the mild to moderate range; however, CDRs ranged from 0.5 to 3. Twelve subjects had a CDR of 0.5; 62 subjects had a CDR of 1; 38 subjects had a CDR of 2; and 19 subjects had a CDR of 3. All but three participants were able to complete the MMSE. The mean MMSE score of 18.5 corresponds to a moderate level of cognitive deficit, but the full range of scores (1–30) was observed. Blessed Dementia Rating Scale ADL scores ranged from 0.5 to 11.5 (mean = 4.92, SD = 2.59). Gender differences in subject characteristics were seen only on the MMSE, with women having significantly lower scores (women: mean = 17.25, SD = 7.14; men: mean = 19.93, SD = 6.34; t=2.21, df=124, p<0.05).

Prevalence of Behavioral Symptoms

Dementia Apathy Interview and Rating (DAIR) scores can range from 0.00 to 3.00, that is, apathetic behavior occurring from almost never to almost always. The scores in our sample covered this entire range, with an average score of 1.20 (SD = 0.72, median = 1.19); an apathy score of one indicates apathetic behaviors occurring on average 4–8 days per month. As the comparability of the mean and median suggests, the distribution was symmetrical and not significantly skewed (skew = 0.271; t=1.28, df=130, NS). The average scores of men and women did not differ (men: mean = 1.29, SD=0.74; women: mean = 1.12, SD = 0.70; t=1.34, df=129, p>0.10).

Behavior Rating Scale for Dementia (BRSD) dysphoria scores can range from 0.00 (no dysphoric symptoms) to 4.00 (indicating dysphoric symptoms on more than one-half the days of the prior month). In our sample, the distribution was from 0.00 to 2.86 (mean = 0.68, SD= 0.72, median=0.43). As the discrepancy between the mean and median suggests, the distribution was highly skewed (skew=1.22; t=5.75, df=130, p<0.01). Over 68% of the sample averaged symptoms of dysphoria fewer than 1–2 days in the preceding month (mean scale score <1.00). Frequency of dysphoric symptoms was higher among women than men (women: mean = 0.83, SD = 0.74; men: mean = 0.52, SD = 0.66; t = −2.51, df=129, p<0.05).

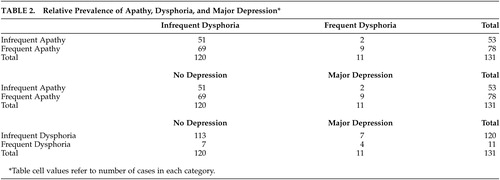

Since the apathy and dysphoria measures do not share the same scale anchors, scores were transformed using a common point on the two scales to permit comparison of apathy and dysphoria severity. Both scales have a rating point representing behaviors occurring approximately 1–2 times per week. This point was used to differentiate between lower and higher levels of apathy (lower defined as an average apathy score <1.00 and higher as a score ≥1.00) and dysphoria (lower defined as an average dysphoria score <2.00 and higher as a score ≥2.00). High frequency of apathy was much more common than high frequency of dysphoria (Table 2). Seventy-eight out of the 131 patients (59.5%) were in the frequent apathy group while only 11 (8.4%) were in the frequent dysphoria group (matched-pair t test for proportions=11.02, df=130, p<0.001). When these categorical variables (high/low apathy or dysphoria) were compared, dysphoria and apathy were not associated with each other (phi=0.14, p>0.10). This lack of association between apathy and dysphoria was also observed when comparing DAIR and BRSD scores (ρ=0.17, df=129, p>0.05).

The DSM–IV depression syndrome is a more complex construct than dysphoria as assessed by the BRSD scale. It includes symptoms other than characteristic mood state and requires the duration of a sufficient number of symptoms to be in excess of 2 weeks. Eleven of the 131 subjects (8.4%) met DSM–IV criteria for major depression in the past year. The most common depression symptoms in this major depression group were sleep disturbances and fatigue (both 82%), followed by sad mood, loss of interest, and psychomotor changes (all 73%), loss of weight (64%), and loss of appetite and guilt feelings (both 54%). Suicidal ideation occurred least frequently (27%). Some of these symptoms of syndromic depression were also common in persons not meeting DSM criteria. The most common were sleep disturbances (41%), loss of interest (35%), and psychomotor changes (28%). Sad mood was reported in fewer than 20% of persons not meeting DSM criteria for a depressive episode.

Relation of Behavioral Symptoms to Disease Severity

The association of apathy and dysphoria with disease severity was evaluated using DAIR and BRSD depression subscale scores (Table 3). Apathy scores increased with stage of dementia (CDR, r=0.47, p<0.01), increasing cognitive impairment (MMSE; r=−0.36, p<0.01), and more functional impairment (Blessed ADL; r=0.56, p<0.01). On the other hand, the frequency of dysphoric symptoms was not significantly related to CDR (r=0.08, p=0.35) or to MMSE (r=0.06, p=0.5), although it was modestly correlated with Blessed ADL scores (r=0.21, p<0.05). The correlations between apathy and these measures of disease severity (CDR, MMSE, and ADL) are significantly higher than the correlation of those disease characteristics with dysphoria (ts≥3.59, df=128, ps<0.0005).

DISCUSSION

The results of this study indicate a striking disparity in the prevalence of apathy, dysphoria, and major depression in AD. Apathy was reported much more frequently than either significant dysphoria or major depression. Fifty nine percent of our sample reported apathy occurring at least 4–8 days per month. Dysphoria at a similar frequency of occurrence or DSM-IV depression was reported for only 8% of the subjects. Consistent with other studies,2,26 measures of apathy and dysphoria were not significantly associated with each other.

As in other investigations,4,5,7 apathy was robustly related to cognitive functioning, activities of daily living and global dementia severity. On the other hand, dysphoric symptoms were unrelated or very weakly related to cognitive or functional aspects of dementia. This differential pattern of associations, together with the strikingly different prevalence of apathy and dysphoria, emphasize the need for the separate assessment of dysphoria and apathy in the evaluation and treatment of persons with dementia. Our findings also suggest current approaches to diagnosis of depression may need to be reevaluated when applied to persons with dementia.

In AD, depressed mood is a much less common symptom than the loss of interest, the other primary symptom of depression in DSM-IV. Loss of interest, however, does not appear to distinguish AD patients with significant affective disorder from those without depression.16 The results of this study support a syndrome based approach to identifying depression in dementia using symptoms of dysphoria (such as sad mood, guilt feelings, low self-esteem and hopelessness) and distinguishing dysphoria from both the apathy syndrome and vegetative symptoms (e.g., sleep disturbances, fatigue, and appetite and weight changes).

Syndromic approaches to the assessment of apathy and dysphoria may help to clarify the research into the underlying pathophysiology of behavioral symptoms. Current research shows apathy in AD to be strongly associated with neuropathology in areas that are components of the anterior cingulate frontal-subcortical circuit (e.g., anterior cingulate, nucleus basalis of Meynert, hippocampus, medial frontal region).31–34 Depression in AD is related to neuropathology in frontal-striatal and subcortical limbic circuits (locus ceruleus, substantia nigra, hippocampus, hypothalamus).35–37 Hypoperfusion or hypoactivity in frontal, parietal, and temporal regions is identified in both apathy and depression.1,34–36,38–42 Apathy appears to involve cholinergic deficits,6 while depression is associated with serotonergic deficits37,43 or an imbalance between dopamine and norepinepherine.37,44 Studies that use discrete assessment of both apathy and dysphoria will permit better characterization of patients and help to clarify differences and potential overlaps in the pathophysiology of these syndromes.

A focus on apathy as distinct from depression will facilitate investigations into specific treatment of the apathy syndrome. Initial studies suggest that apathy in older adults may respond to the use of psychostimulants (e.g., methylphenidate)45–47 or cholinergic therapies,48–52 likely due to their enhancement of prefrontal cortical activity. Distinguishing these syndromes is also important as some medication for depression can worsen apathy; for example, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors may increase apathy and withdrawal from engagement with the environment.45,53 Discrimination of apathy and dysphoria will permit better precision in characterizing patients in both clinical and research settings, leading to improvements in the pharmacological management of behavior symptoms in AD.

In summary, our findings illustrate a number of significant differences between apathy and dysphoria. Apathy in AD occurs more frequently than dysphoria and is much more strongly associated with disease characteristics and functional impairment. Although apathy and depression can be confused using other approaches to assessment, this study demonstrates that these syndromes are discriminable. Our findings suggest that discrete assessment of apathy and dysphoria syndromes may be of greater utility than traditional conceptualizations of depression in advancing both treatment and understanding of behavior symptoms in AD.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was also supported by NIA grant P50-AG08012.

The authors thank Carla Cashman and Thomas Fritsch for their assistance.

|

|

|

1 Landes AM, Sperry SD, Strauss ME, et al: Apathy in alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc 2001; 49:1700–1707Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2 Mega MS, Cummings JL, Fiorello T, et al: The spectrum of behavioral changes in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurol 1996; 46:130–135Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3 Bozzola FG, Gorelick PB, Freels S: Personality changes in alzheimer’s disease. Arch Neurology 1992; 49:297–300Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4 Devanand DP, Brockington CD, Moody BJ, et al: Behavioral syndromes in alzheimer’s disease. Int Psychogeriatr 1992; 4(suppl 2):161–184Google Scholar

5 Freels S, Cohen D, Eisdorfer C, et al: Functional status and clinical findings in patients with alzheimer’s disease. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 1992; 47:M177-M182Google Scholar

6 Cummings JL, Back C: The cholinergic hypothesis of neuropsychiatric symptoms in alzheimer’s disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 1998; 6(suppl 1):S64-S78Google Scholar

7 Gilley DW, Wilson RS, Bennett DA, et al: Predictors of behavioral disturbance in alzheimer’s disease. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 1991; 46:P362-P371Google Scholar

8 Burns A, Folstein S, Brandt J, et al: Clinical assessment of irritability, aggression, and apathy in Huntington and alzheimer disease. J Nerv Ment Dis 1990; 178:20–26Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9 Campbell JJ, Duffy JD: Treatment strategies in amotivated patients. Psychiatr Annals 1997; 27:44–49Crossref, Google Scholar

10 Kaufer DI, Cummings JL, Christine D, et al: Assessing the impact of neuropsychiatric symptoms in alzheimer’s disease: The neuropsychiatric inventory caregiver distress scale. J Am Geriatr Soc 1998; 46:210–215Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11 Greene JG, Smith R, Gardiner M, et al: Measuring behavioral disturbance of elderly demented patients in the community and its effects on relatives: a factor analytic study. Age Ageing 1982; 11:121–126Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12 Burns A, Jacoby R, Levy R: Psychiatric phenomena in alzheimer’s disease. III disorders of mood. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1990; 6:371–376Crossref, Google Scholar

13 Merriman AE, Aronson MK, Gaston P, et al: The psychiatric symptoms of alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc 1988; 36:7–12Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14 Ballard CG, Bannister C, Oyebode F: Depression in dementia sufferers. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1996; 11:507–515Crossref, Google Scholar

15 Ross LK, Arnsberger P, Fox PJ: The relationship between cognitive functioning and disease severity with depression in dementia of the alzheimer’s type. Aging Ment Health 1998; 2:319–327Crossref, Google Scholar

16 Ballard CG, Bannister C, Solis M, et al: The prevalence, associations and symptoms of depression amongst dementia sufferers. J Affect Disord 1996; 36:135–144Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17 Cummings JL, Ross W, Absher J, et al: Depressive symptoms in alzheimer disease: assessment and determinants. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 1995; 9:87–93Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18 Migliorelli R, Teson A, Sabe L, et al: Prevalence and correlates of dysthymia and major depression among patients with alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:37–44Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19 Wragg RE, Jeste DV: Overview of depression and psychosis in alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry 1989; 146:577–587Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20 Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, et al: The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: Comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology 1994; 44:2308–2314Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21 American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

22 Tariot PN, Mack JL, Patterson MB, et al: The behavior rating scale for dementia of the consortium to establish a registry for alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:1349–1357Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23 Marin RS, Firinciogullari S, Biedrzycki RC: The sources of convergence between measures of apathy and depression. J Affect Disord 1993; 28:117–124Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24 Marin RS, Biedrzycki RC, Firinciogullari S: Reliability and validity of the apathy evaluation scale. Psychiatry Res 1991; 38:143–162Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25 Hamilton MA: A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960; 23:56–62Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26 Strauss ME, Sperry SD: An informant-based assessment of apathy in alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol 2002; 15:176–183Medline, Google Scholar

27 McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, et al: Clinical diagnosis of alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA work group under the auspices of the Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 1984; 34:939–944Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28 Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR: Mini-Mental State: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975; 12:189–198Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29 Esiri M: The basis for behavioral disturbances in dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1996; 61:127–130Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30 Blessed G, Tomlinson BE, Roth M: The association between quantitative measures of dementia and of senile change in the cerebral grey matter of elderly subjects. Br J Psychiatry 1968; 114:797–811Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31 Forstl H, Burns A, Levy R, et al: Neuropathological correlates of behavioral disturbance in confirmed alzheimer’s disease. Br J Psychiatry 1993; 163:364–368Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32 Burns A, Forstl H: The institute of psychiatry alzheimer’s disease cohort: part 2B, Clinicopathological observations. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1996; 11:321–327Crossref, Google Scholar

33 Tekin S, Mega MS, Masterman DM, et al: Orbitofrontal and anterior cingulate cortex neurofibrillary tangle burden is associated with agitation in alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol 2001; 49:355–361Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34 Starkstein SE, Sabe L, Vasquez S, et al: Neuropsychological, psychiatric, and cerebral perfusion correlates of leukoaraiosis in alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1997; 63:66–73Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35 Mayberg HS: Clinical correlates of PET- and SPECT-identified defects in dementia. J Clin Psychiatry 1994; 55[11, suppl]:12–21Google Scholar

36 Ebmeier KP, Prentice N, Ryman A, et al: Temporal lobe abnormalities in dementia and depression: a study using high resolution single photon emission tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1997; 63:597–604Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37 Cummings JL: Cognitive and behavioral heterogeneity in alzheimer’s disease: seeking the neurobiological basis. Neurobiol Aging 2000; 21:845–861Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38 Craig AH, Cummings JL, Fairbanks L, et al: Cerebral blood flow correlates of apathy in alzheimer’s disease. Arch Neurol 1996; 53:1116–1120Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39 Ott BR, Noto RB, Fogel BS: Apathy and loss of insight in alzheimer’s disease: A spect imaging study. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1996; 8:41–46Link, Google Scholar

40 Benoit M, Dygai I, Migneco O, et al: Behavioral and psychological symptoms in alzheimer’s disease: relation between apathy and regional cerebral perfusion. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 1999; 10:511–517Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41 Hirono N, Mori E, Ishii K, et al: Frontal lobe hypometabolism and depression in alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 1998; 50:380–383Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42 Lopez OL, Zivkovic S, Smith G, et al: Psychiatric symptoms associated with cortical-subcortical dysfunction in alzheimer’s disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2001; 13:56–60Link, Google Scholar

43 Meltzer CC, Price JC, Mathis CA, et al: PET imaging of serotonin type 2A receptors in late-life neuropsychiatric disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:1871–1878Medline, Google Scholar

44 Zubenko GS, Hughes HB, Stiffler JS: Clinical and neurobiological correlates of DXS1047 genotype in alzheimer’s disease. Biol Psychiatry 1999; 46:173–181Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

45 Marin RS, Fogel BS, Hawkins J, et al: Apathy: A treatable syndrome. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1995; 7:23–30Link, Google Scholar

46 Weiner MF, Debus JR, Goodkin K: Pharmacological management and treatment of dementia and secondary symptoms, in The Dementias: Diagnosis and Management, Edited by Weiner MF. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1991, pp 135–166Google Scholar

47 Roccaforte WH, Burke WJ: Use of psychostimulants for the elderly. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1990; 41:1330–1333Medline, Google Scholar

48 Rosler M: The efficacy of cholinesterase inhibitors in treating the behavioural symptoms of dementia. Int J Clin Pract Suppl 2002; 127:20–36Medline, Google Scholar

49 Cummings JL, Nadel A, Masterman D, et al: Efficacy of metrifonate in improving the psychiatric and behavioral disturbances of patients with alzheimer’s disease. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 2001; 14:101–108Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

50 Levy ML, Cummings JL, Kahn-Rose R: Neuropsychiatric symptoms and cholinergic therapy for alzheimer’s disease. Gerontology 1999; 45:15–22Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

51 Mega MS, Masterman DM, O’Connor SM, et al: The spectrum of behavioral responses to cholinesterase inhibitor therapy in alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 1999; 56:1388–1393Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

52 Kaufer D, Cummings JL, Christine D: Differential neuropsychiatric symptom responses to tacrine in alzheimer’s disease: relationship to dementia severity. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1998; 10:55–63Link, Google Scholar

53 Hoehn-Saric R, Lipsey JR, McLeod DR: Apathy and indifference in patients on fluvoxamine and fluoxetine. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1990; 10:343–345Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar