Loss of Insight and Functional Neuroimaging in Frontotemporal Dementia

Abstract

Loss of insight is a diagnostic criterion for frontotemporal dementia. It is associated with hypoperfusion/hypometabolism in the right hemisphere, particularly the frontal lobe. Loss of insight is often an anosodiaphoria (i.e., lack of concern) rather than an anosognosia (i.e., decreased awareness).

Loss of insight is common in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and other dementias.1–7 Clinically, loss of insight means a denial or unawareness of symptoms or an unconcern about the consequences of symptoms. Clinicians frequently use loss of insight synonymously with anosognosia, a term originally used to describe reduced awareness of hemiplegia in stroke patients and is now applied to the reduced awareness of any symptom.9 In dementia, the extent of anosognosia varies according to the type of dysfunction, often being worse for memory and other cognitive functions.1,2 Loss of insight in dementia occurs independent of the presence of depression or the psychological mechanisms of the denial of illness.9

Loss of insight is particularly characteristic of early frontotemporal dementia (FTD).10 Consensus criteria for FTD include loss of insight as a core diagnostic feature of the disorder,10 and patients with FTD display a greater loss of insight into illness early in their dementia when compared to patients with AD11 Compared to other FTD patients, those patients with greater right frontal disease have more apathy.12 This finding suggests that loss of insight in FTD may result from right frontal disease and a loss of concern for their illness or their behavioral changes rather than a true anosognosia. This article examines the nature and association of loss of insight with the changes on functional neuroimaging among patients with FTD.

METHOD

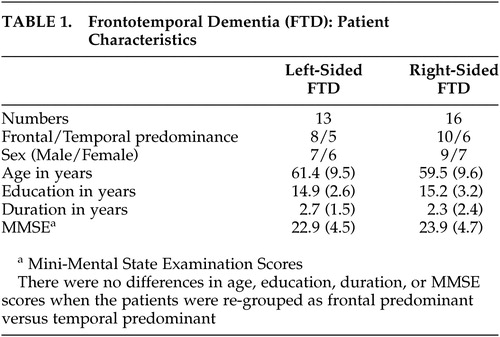

Twenty-nine patients met diagnostic criteria for early FTD based on consensus criteria (Table 1).10 Patients were recruited from the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) Focal-type Dementia Clinic. Each patient agreed to participate in a program on FTD at the UCLA Alzheimer’s Disease Center and signed an approved, informed consent. The core criteria necessary for a clinical diagnosis of FTD are deceptive at onset. Gradual progression of early decline in social interpersonal conduct, early impairment in regulation of personal conduct, early emotional blunting, and early loss of insight takes place.10 The clinical diagnosis in this study was corroborated by the presence of frontal or anterior temporal predominant changes on functional neuroimaging.

As part of the evaluation, the FTD patients were graded on their responses to the insight question (“Tell me why you are here?”) taken from the Consortium to Establish a Registry in AD (CERAD).13 Three additional questions were used to generate responses to the CERAD question. The three questions were: 1) Do you have an illness or a problem that requires medical attention? 2) Is your behavior significantly different now, compared to a few years ago? 3) Do family/friends think that you have an illness or that something is wrong with you?” The patients’ responses were graded on a 4-point Likert scale of insight into illness and implications. The grading scale was: normal or awareness of an illness or a problem requiring medical attention (score=3); partial awareness or unawareness of illness or problem requiring medical attention but aware of a significant change in behavior (score=2); unawareness or denial of both an illness and a behavioral change but aware that family and friends think that something is wrong (score=1); total unawareness or concern about health or behavior (score=0). Finally, patients were analyzed regarding their knowledge of their behavior, and whenever they endorsed an awareness of illness or behavioral changes, they were asked to describe their degree of concern.

The results of the CERAD insight question were analyzed in terms of the predominant localization of changes on functional neuroimaging. All of these early FTD patients had asymmetric hypoperfusion or hypometabolism on single photon emission tomography (SPECT) images or positron emission tomography (PET) scans. Based on visual inspection of prominence of hypoperfusion or hypometabolism, the images were independently divided into left versus right hemispheric laterality and frontal versus temporal quadrants by neuroimagers unfamiliar with the patients or their clinical characteristics. These findings were compared with the results of the CERAD insight question using factorial analysis of variance (ANOVA).

RESULTS

The characteristics of the FTD patients are summarized in Table 2. Most patients denied having an illness or a problem that required medical attention. However, all patients were able to describe their behaviors when analyzed. The patients could not convey a commensurate concern about the consequences of their behavioral symptoms and usually felt that these symptoms did not represent disturbances, abnormalities, or significant changes from their usual patterns of behavior.

Representative behavioral comments illustrated the nature of patients’ loss of insight. One patient stated, “I am shallow now…this bothers other people but not me.” Another patient would go into stores and restaurants and leave without paying for goods and services. She could describe these episodes and the potential consequences, but she was not distressed or concerned about her behavior. Several other patients conveyed the same lack of concern for doing the right thing despite knowing the difference. A patient with compulsive-like behaviors stated, “I do not care if people do not like it.” Another patient, who had become sexually disinhibited and libertine, described specific encounters. She endorsed them as unacceptable but did not express appropriate concern, even for the potential impact on her children.

On the SPECT and PET scans, 13 patients had predominant left-sided hypoperfusion or hypometabolism, and 16 had predominant right-sided hypoperfusion or hypometabolism. Ten of the right-sided patients had greater frontal hypoperfusion or hypometabolism than temporal hypoperfusion or hypometabolism, and six had greater temporal changes. Eight of the left-sided patients had more frontal changes than temporal changes, and five had greater temporal changes. The main effect of the ANOVA was significant (F(2, 25) = 16.36, p<0.001), and there was a laterality effect (F(1, 25) = 19.81, p<0.01) and a frontal versus temporal predominance effect (F(1, 25) = 13.36, p<0.01) but no statistically significant interaction. Despite the lack of a statistically significant interaction, the greatest loss of insight occurred among the right frontal predominant FTD patients.

DISCUSSION

It is not surprising that FTD is characterized by loss of insight.10 In dementia, patients who lack insight of their cognitive and functional deficits may be indifferent about their emotional response toward their condition.5 In the present, we found that the loss of insight in FTD was greatest in those with right hemispheric hypoperfusion/hypometabolism, particularly in the frontal lobe. In many of these patients, the loss of insight could be more properly described as indifference or anosodiaphoria rather than anosognosia.

Among the dementias, investigators have primarily studied loss of insight in AD, where it is related to deficits in frontal functions, especially on the right.4,6 In AD, the most consistent correlations between impaired insight and neuropsychological tests were regarding frontal-executive tasks such as the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test, verbal fluency, Luria’s graphic series, Mazes, and the Trailmaking Tests.2,14 Loss of insight was highly correlated with a frontal score that included frontal behaviors such as prehension, utilization, imitation, inertia, and indifference.14 In addition, most SPECT studies in AD patients with loss of insight report significant blood flow deficits in the right hemisphere, especially the frontal inferior and dorsolateral areas.5,6,15

Loss of insight can result from various mechanisms. Anosognosia refers to a true recognition defect in which the patient is unaware of or has impaired knowledge of acquired symptoms and behaviors.8 Anosognosia generally results from damage to the right inferior parietal lobule and is often defined as a discrepancy between a patient’s report of disability and any objective evidence regarding impairment. In contrast, anosodiaphoria refers to the condition in which patients are unconcerned with or significantly minimize the extent of their deficits.8

There are several limitations to this preliminary study. First, the numbers of FTD patients per quadrant (laterality and frontotemporal) were relatively small and may have masked a frontal-right hemispheric interaction. Second, the addition of neuropsychological measures could lend validity to the regional findings from functional neuroimaging. Finally, although the method of image analysis based on laterality and frontotemporal quadrants allows for a simple categorization of predominant lateralization and localization, it restrains the capacity to consider multiple regions of change.

In conclusion, loss of insight in FTD may be a function of right hemisphere disease, especially in the frontal lobe, and is at least partially due to patients’ lack of concern for their illness or symptoms. Characterization of the nature of loss of insight in FTD has management implications, as it affects functional performance and decline. Further studies into the relation between loss of insight and focal pathophysiology may clarify the underlying mechanisms responsible for loss of insight from right frontal dysfunction.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by NIA P01 AG19724–01A1 (Bruce L. Miller, P.I.) and the UCLA Alzheimer’s Disease Center.

|

|

1 Green J, Goldstein FC, Sirockman BE, et al: Variable awareness of deficits in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol 1993; 6:159–165Google Scholar

2 Ott BR, Lafleche G, Whelihan WM, et al: Impaired awareness of deficits in Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 1996; 10:68–76Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3 Kotler-Cope S, Camp CJ: Anosognosia in Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 1995; 9:52–56Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4 Lopez OL, Becker JT, Somsak D, et al: Awareness of cognitive deficits and anosognosia in probable Alzheimer’s disease. Eur Neurol 1994; 34:277–282Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5 Ott BR, Noto RB, Fogel BS: Apathy and loss of insight in Alzheimer’s disease: a SPECT imaging study. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1996; 8:41–46Link, Google Scholar

6 Reed BR, Jagust WJ, Coulter L: Anosognosia in Alzheimer’s disease: relationship to depression, cognitive function, and cerebral perfusion. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 1993; 15:231–244Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7 Vasterling JJ, Seltzer B, Foss JW, et al: Unawareness of deficit in Alzheimer’s disease-domain specific differences and disease correlates. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol 1995; 8:26–32Google Scholar

8 Tranel D: Functional neuroanatomy. Neuropsychological correlates of cortical and subcortical damage, in The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 4th ed, by Yudofsky SC, Hales RE. Ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc, 2002, pp 93Google Scholar

9 Smith CA, Henderson VW, McCleary CA, et al: Anosognosia and Alzheimer’s disease: the role of depressive symptoms in mediating impaired insight. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 2000; 22:437–444Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10 Neary D, Snowden JS, Gustafson L, et al: Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: a consensus on clinical diagnostic criteria. Neurology 1998; 51:1546–1554Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11 Gustafson L: Clinical picture of frontal lobe degeneration of non-Alzheimer type. Dementia 1993; 4:143–148Medline, Google Scholar

12 Boone KB, Miller BL, Swartz R, Lu P, Lee A: Relationship between positive and negative symptoms an neuropsychological scores in frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2003; 9:698–709Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13 Welsh KA, Butters N, Mohs RC, et al: The consortium to establish a registry in Alzheimer’s disease (CERAD), part V, A normative study of the neuropsychological battery. Neurology 1994; 44:609–614Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14 Michon A, Deweer B, Pillon B, et al: Relation of anosognosia to frontal lobe dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1994; 57:805–809Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15 Starkstein SE, Vazquez S, Migliorelli R, et al: A single-photon emission computed tomographic study of anosognosia in alzheimer’s disease. Arch Neurol 1995; 52:415–420Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar