Depression and Stages of Huntington’s Disease

Abstract

Individuals with manifest Huntington’s disease (HD) were interviewed with regard to the presence, frequency, and severity of depression symptoms to better characterize depressed mood across the disease course in HD. Rates of depression were more than twice that found in the general population. One-half reported that they had sought treatment for depression, and more than 10% reported having at least one suicide attempt. The proportion of HD patients endorsing significant depression diminished with disease progression. Despite the public health impact of depression, available treatments are underutilized in HD, and research is needed to document the efficacy and effectiveness of standard depression treatments in this population.

Depression is one of the most common psychiatric disorders in the general population and a leading cause of disability, costing an estimated $44 billion per year.1 The presence of depression contributes to medical morbidity, mortality, personal suffering, family disruption, and cost of care.2,3 Even mild depression can affect emotional, social, and occupational functioning. Despite the public health impact of depression, available, and even efficacious, treatments are underutilized or incorrectly utilized.4–7 The importance of undiagnosed and untreated depression has become of such prominence in the United States that the Agency for Healthcare Research developed a U.S. Preventive Services Task Force to recommend clinical practice guidelines for comprehensive depression screening in general medical practice.

Depression is a common feature of many progressive, terminal illnesses. One study showed that patients with any medical diagnosis were twice as likely to have depression than patients without a medical diagnosis.8 Rates of depression in neurological diseases have long been recognized as higher than expected, however, and much debate has ensued about the possible biological versus reactive components of this depression. For instance, lifetime rates of depression in patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD) approach 70%,9 and depression in PD is associated with greater cognitive impairment,10 more rapid disease progression,9 and increased disability.11

Whereas contributions to the development of depression in brain disease are multifactorial and likely include psychosocial factors (i.e., adjustment to a terminal illness and increased disability), the neuropathophysiology of depression suggests a preeminent role for biological mechanisms. Mood disorders are often associated with basal ganglia abnormality12,13 or damage acquired through stroke,14 traumatic brain injury15 developmental disorders,16 or degenerative disease.17–19 Hence, further exploration of depression in brain (particularly basal ganglia) diseases may offer insight into mechanisms of depression.

Huntington’s disease (HD) is an autosomal-dominant terminal illness characterized by deterioration in motor, cognitive, and emotional function. The disease is caused by an abnormal number of repeats of the trinucleotide sequence cytosine-adenine-guanine (CAG) in the gene IT-15 on chromosome 4. CAG repeats of more than 36 result in HD if an individual lives a normal lifespan. Longer CAG repeats are associated with earlier disease onset. Estimates of the prevalence of depression in Huntington’s disease (HD) vary widely, ranging from 9% to 63%20 with several studies suggesting rates between 40 and 50%.21,22 Despite widespread occurrence, depression in HD has received minimal consideration. Since the diagnosis of HD typically implies a progressive, embarrassing, and disabling movement disorder in the prime of life accompanied by serious cognitive deterioration and a 50% probability of transmitting the same disorder to one’s children, high rates of depression have become a readily accepted component of the disease. Indeed, suicide rates over five times that found among the general population have been considered “not surprising…given the often agonizing clinical course of HD and the common occurrence of serious depression.”23 Unlike Huntington’s disease itself, however, depression is typically a treatable disorder.2,24

Previous research suggests that psychiatric symptoms, particularly depression, are a significant prognostic component (Langbehn, unpublished data), if not the presenting complaint,25 in the majority of HD patients and may present up to 20 years prior to disease onset.21 Depression in HD is not correlated with cognitive impairment, motor symptoms, or CAG repeat length;26,27 however, depressive symptoms are associated with specific cognitive abilities28 and more rapid decline in functional ability.29

The progression of symptoms in HD is not well understood. Penney et al.30 reported that motor abnormalities progress from eye abnormalities early in the disease followed by involuntary choreiform movements that decrease in mid-illness as rigidity and bradykinesia increase. With regard to cognitive performance, psychomotor abilities show the most significant and consistent decline across disease progression; difficulties in visuospatial and memory abilities occur later in HD.31 Few studies have assessed the progression of psychiatric symptoms in HD; however, a study by Kirkwood et al.32 suggested that sadness and depression were two of the earliest symptoms at HD onset by report of first-degree relatives of participants. Assessment of the time course of clinical symptoms in relationship to disease severity (functional impairment) may prove informative in assigning care programs for persons with HD.

The current study hopes to build on past research characterizing depressive symptoms in individuals with HD by increasing sample size from previous studies. In addition, this study assessed depressive symptoms in HD patients by degree of disability (stage of illness) and is one of the few studies to assess current endorsement of depressive symptoms in patients diagnosed with HD.

METHOD

Procedure

After obtaining informed consent, all participants were administered the Unified Huntington Disease Rating Scale (UHDRS)33 as part of the standard evaluation procedures at 57 Huntington Study Group (HSG) sites in North America, Europe, and Australia. Data from individual sites were combined at the University of Rochester.

Measure

The UHDRS is a standardized clinical rating scale used to assess motor, cognitive, behavioral, and functional capacity symptoms of Huntington’s disease. The motor scale assesses eye movements, motor control, rigidity, bradykinesia, dystonia, chorea, and gait. The cognitive section is composed of a test of verbal fluency,34 the Symbol Digit Modalities Test,35 and the Stroop Test.36 The behavior section assesses the frequency and severity of 11 psychiatric symptoms (e.g., depression, delusions). Frequency and severity of these symptoms are scored on a scale from 0 to 4 with lower numbers indicating less frequent and less severe psychiatric symptoms. A brief health history is obtained which asks whether treatment has been sought for depression and whether any suicide attempts have been made.

The Total Functional Capacity (TFC) scale37 is a standard measure of functional capacity often employed in HD research. The TFC scale consists of five items assessing engagement in occupation, capacity to handle financial affairs, capacity to manage domestic responsibilities, capacity to perform activities of daily living, and the type of residential care provided. Scores range from 0 to 13, with higher scores indicative of higher functioning and greater independence. TFC score serves as the basis in determination of current stage of illness. Specific cutpoints for stages are described by Shoulson and Fahn.37

A factor analysis of the UHDRS revealed 15 nonoverlapping factors within the UHDRS.29 The factor analysis revealed one “depression” factor consisting of frequency and severity ratings for the following UHDRS items: sad mood, low self-esteem, and anxiety. These items were the primary psychiatric items of interest in the current study. Individual scores for these items were computed by multiplying frequency by severity for each item. Participants were said to endorse the depressive symptom if their severity times frequency value was greater than 3. This score was chosen to eliminate individuals who reported experiencing “slight” or “questionable” levels of these symptoms.

The proportion of individuals endorsing symptoms of depression was compared across stages using a nonparametric, two-tailed chi-square test. A nonparametric test was employed due to differences in sample sizes between groups and non-normal distribution of depressive symptoms. Post hoc pairwise nonparametric chi-square analyses were also employed.

Participants

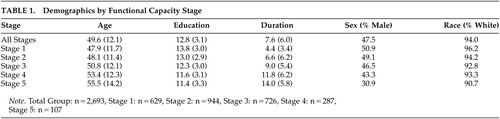

All participants (N=2,835) received a diagnosis of definite HD based upon the presence of motor abnormalities observed during the standardized neurological exam of the UHDRS. Only individuals with disease onset at 20 years of age or older were included in the current study to exclude cases with juvenile onset and, hence, variable clinical presentation. Subjects were classified to one of five HD stages based on their TFC scores. Demographic information can be found in Table 1. There were significant differences in age (F=22.812, df=4, 2751, p≤0.001), duration of illness (F=126.728, df=4, 2193, p≤0.001), and education (F=36.047, df=4, 2425, p≤0.001) between stages. As expected, participants’ age and duration of illness were higher in later stages of HD. Individuals in later stages of HD had fewer years of education. This difference may be due to cohort effects.

RESULTS

A relatively small percentage of individuals were missing information regarding sad mood (3.7%), low self-esteem (4.4%), and anxiety (4.4%). Individuals who were missing information were significantly more likely to be more disabled (stage of illness), have longer disease duration, and have less education. Interestingly, individuals did not differ on current age. Although not significant, rates of past suicide attempts (14.9%), and history of treatment for depression (53.2%) were slightly greater in the participants who did not complete the UHDRS items about current mood.

Approximately one-half (47.5%) of participants were male with a mean age of 49.6 and an average duration of illness of 7.6 years. (See Table 1 for more information.) Participants reported a significant depression history. One-half (50.3%) of participants reported seeking treatment for depression, and 10.3% of participants reported having at least one suicide attempt.

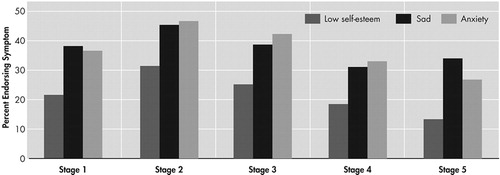

The proportion of individuals endorsing symptoms of depression (i.e., sad mood, low self-esteem, and anxiety), grouped by stage of illness based on TFC score, is presented in Figure 1. Overall the endorsement of depressive symptoms was high among individuals with manifest HD (40.5% of the sample endorsed sad mood, 25.0% endorsed low self-esteem, and 41.0% endorsed symptoms of anxiety). Chi-square tests of independence revealed significant differences across stages for incidence of all three symptoms of depression (sad mood, χ2=20.1, df=4, p<0.001; low self-esteem, χ2=34.1, df=4, p<0.001; and anxiety, χ2=32.1, df=4, p<0.001). Visual analysis of the data suggested that a higher proportion of individuals in stage 2 endorsed depressive symptoms than in any other stage. Post hoc pairwise chi-square tests were run to assess the significance of these apparent differences. These analyses revealed that significantly higher rates of depressive symptoms were reported by individuals in stage 2 when compared to individuals in stage 1 (sad mood χ2=7.97, df=1, p<0.01; low self-esteem χ2=16.2, df=1, p<0.001; and anxiety χ2=14.0, df=1, p<0.001). A second post hoc analysis was run to assess the rates of depressive symptoms in stages 2 through 5. Chi-square analyses suggest that significantly lower rates of depressive symptoms were reported in later stages (sad mood χ2=18.8, df=3, p<0.001; low self-esteem χ2=27.9, df=3, p<0.001; and anxiety χ2= 26.7, df=3, p<0.001). The proportion of individuals endorsing symptoms was generally lower in each stage beyond stage 2, although a nonsignificant increase in sad mood was observed from stage 4 to stage 5 (χ2=.469, df=1, p=0.493; see Figure 1).

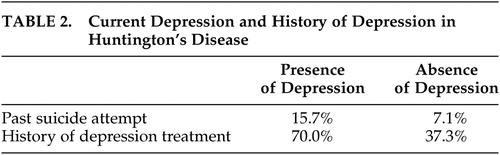

When the HD sample was divided into those with (versus those without) a history of depression and/or suicide attempt, significant differences between groups emerged (see Table 2). HD patients who endorse current depressive symptoms are significantly more likely to have a history of treatment for depression and to have past suicide attempts. Those endorsing current symptoms of depression are twice as likely as those who are not endorsing symptoms of depression to have attempted suicide in the past. These findings confirm that our relatively brief assessment of depression has some concurrent validity and ability to identify HD patients in whom depression is a significant component of the illness.

DISCUSSION

Consistent with past research, findings demonstrate high rates of depressive symptoms reported by individuals with HD. Over 40% of patients endorsed having current significant symptoms of depression, and over 50% had received treatment in the past. More than 10% had made a suicide attempt. These data extend previous research by showing that rates of depressive symptoms vary across disease progression. Findings in this large cohort of HD patients suggest that depressive symptoms increase during the initial stages of disease and peak during stage 2. Depressive symptoms may slowly diminish during middle and later stages of the disease.

There are several potential explanations for the observed data. Research assessing depression in Parkinson’s disease suggests that depression is associated with increased disability.11 Individuals in stage 2 are more disabled than individuals in stage 1. Progression between these stages is associated with cessation of employment and often the revocation of driving privileges. This loss of functioning and the consequent increased reliance on others may be associated with decreased mood. Alternatively (or additionally), progression of disease is associated with increased pathology of the basal ganglia. Dysfunction in frontal-subcortical circuits is often implicated in depression etiology,38 and it is possible that the probability of depression increases with brain dysfunction.

The mechanisms responsible for depression in HD are unclear. It is likely that the etiology of depression in HD is twofold. First, environmental factors such as adjustment to a terminal illness, increased disability, and grief may contribute to depression onset in HD. Second, the circuitry affected by HD may provide a biological component to depression etiology. Depression has previously been associated with dysfunction in frontal cortices including dorsolateral prefrontal cortices, orbitofrontal cortices, and anterior cingulate cortices.38,39 Mayberg et al.40,41 have demonstrated that individuals with HD or Parkinson’s disease (PD) with depression exhibit hypometabolism in the orbitofrontal-inferior prefrontal cortex compared to individuals with HD or PD without depression. These studies suggest that depression is associated with dysfunction of the frontal lobes. HD is associated with atrophy of the caudate nucleus and putamen, which are critical components in frontal subcortical circuits described by Alexander et al.42,43 These circuits suggest that disruption at any point in the circuit can result in dysfunction of the entire circuit, which suggests that the neuropathology of HD may result in increased vulnerability to depression.

Findings suggesting that rates of depressive symptoms decrease during the middle and later stages of HD (when disability and brain pathology increase) appear somewhat counterintuitive. Patients in late stage HD are increasingly more disabled and dependent upon others for simple tasks such as eating, bathing and dressing, and neuron loss in the basal ganglia has been estimated at 60%.44 There is some indication that mood is less routinely assessed in patients with more advanced HD. For instance, missing data increased with disease progression in this large cohort and may account for the overall increase in the average level of depressed symptoms in later stages of HD. If true, this may indicate a limitation in our current practice of mood management in neurology. It is well known that later stages of neurological disease pose a significant limitation in terms of bedside assessment. Decreased verbal output coupled with increased obvious effort and frustration may limit the ease with which psychiatric and/or behavioral symptoms are assessed. Bivariate correlations conducted between the total depression factor score and performance on the test of verbal fluency revealed a significant association (r=.05, p<0.04), suggesting that lower rates of depression may be an artifact of verbal dysfluency. Further research is indicated to validate this observation and test alternative assessment mechanisms for mood disorder in later stage neurological illness.

There are some alternative explanations for our finding of less depression in advanced HD, however. It is possible that individuals in later stages of disease may demonstrate adaptation to illness and acceptance of their diagnosis and future. In addition, insight may become so impaired with later stage of HD that rates of depressive symptoms do indeed decrease as patients are no longer able to assess their current disability. Finally, the measures used to assess depressive symptoms in the current study are somewhat limited. It is possible that depression in HD may be better elucidated with a more comprehensive assessment of depression including measures of changes in sleep, apathy, and anhedonia.

Longitudinal studies are needed to replicate the pattern of depression reported in this large cross-sectional, study of HD. It is possible that rates of depressive symptoms may represent a cohort effect and vary in future samples. Future longitudinal studies of psychiatric symptoms in HD will be helpful in understanding the progression of depressive symptoms in real time.

These results complement and extend past research in depression and HD. To our knowledge, this is the largest sample size studied to date. This is the first study to examine HD by stage of disease (and level of disability) rather than duration of illness.32 This study assessed current symptoms of depression with a standardized interview rather than relying on retrospective reports.

High rates of depressive symptoms are found in patients diagnosed with HD. Rates of persons acknowledging symptoms of depression are highest in the first stages of disease and can peak during stage two. The validation of decreasing rates of depression in later stages of HD requires replication with longitudinal studies and novel measurement techniques to rule out communication difficulties, adaptation to disability, and poor insight as contributors to depression in late stage illness. Future research is required to assess whether conventional treatment paradigms for depression (both pharmacological and therapeutic) are efficacious and effective in persons with HD. Despite a growing body of research in the general population, it remains unknown whether selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or cognitive behavior therapy are useful in HD.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Presented in part at the American Neuropsychiatric Association 13th Annual Meeting, March 10–12, 2002, La Jolla, Calif.

Supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke grant #40068 and the National Institute of Mental Health grant #01579 to Jane S. Paulsen, National Institute of Mental Health grant #65830 to Carissa Nehl, and the Huntington’s Disease Society of America, the Huntington’s Society of Canada, and the Hereditary Disease Foundation grants to the Huntington Study Group.

FIGURE 1. Percent of HD Patients Endorsing Depressive Symptoms by Stage

|

|

1 Stewart WF, Ricci JA, Chee E, et al: Cost of lost productive work time among US workers with depression. Int 2003; 289:3135–3144Google Scholar

2 Cooper-Patrick L, Crum RM, Ford DE: Characteristics of patients with major depression who received care in general medical and specialty mental health settings. Med Care 1994; 32:15–24Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3 Hays RD, Wells KB, Sherbourne CD, et al: Functioning and well-being outcomes of patients with depression compared with chronic general medical illnesses. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52:11–19Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4 Barraclough BM: Suicide in the elderly: Recent developments in psychogeriatrics. Br J Psychiatry 1971; 6(suppl):87-97Google Scholar

5 Miller M: Geriatric suicide: the Arizona study. Gerontologist 1976; 18:488–495Crossref, Google Scholar

6 Katon W, Robinson P, Von Korff M, et al: A multifaceted intervention to improve treatment of depression in primary care. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53:924–932Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7 Simon GE, VonKorff M, Barlow W: Health care costs of primary care patients with recognized depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52:850–856Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8 Luber MP, Hollenberg JP, WIlliams-Russo P, et al: Diagnosis, treatment, comorbidity, and resource utilization of depressed patients in a general medical practice. Int J Psychiatry Med 2000; 30:1–13Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9 Starkstein SE, Bolduc PL, Mayberg HS, et al: Cognitive impairments and depression in Parkinson’s disease: a follow up study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1990; 53:597–602Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10 Tandberg E, Larsen JP, Aarsland D, et al: Risk factors for depression in Parkinson disease. Arch Neurol 1997; 54:625–630Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11 Starkstein SE, Mayberg HS, Leiguarda R, et al: A prospective longitudinal study of depression, cognitive decline, and physical impairments in patients with parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1992; 55:377–382Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12 Krishnan KR, McDonald WM, Escalona PR, et al: Magnetic resonance imaging of the caudate nuclei in depression: preliminary observations. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:553–557Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13 Rabins PV, Pearlson GD, Aylward E, et al: Cortical magnetic resonance imaging changes in elderly inpatients with major depression. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:617–620Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14 Starkstein SE, Robinson RG: Depression in Neurologic Disease. Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1993, p 246Google Scholar

15 Koponen S, Taiminen T, Portin R, et al: Axis I and II psychiatric disorders after traumatic brain injury: A 30-year follow-up study. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:1315–1321Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16 Jankovic J: Tourette’s syndrome. N Engl J Med 2001; 345:1184–1192Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17 Kostíc VS, Stefanova E, Dragaseíc N, et al: Diagnosis and treatment of depression in Parkinson’s disease, in Mental and Behavioral Dysfunction in Movement Disorders. Edited by Bédard MA, Agid Y, Chouinard S, et al. Totowa, NJ, Humana Press, 2003, pp 351-368Google Scholar

18 Paulsen JS, Ferneyhough K, Nehl C, et al: Critical periods of suicide risk in Huntingtonn’s disease. Am J Psychiatry 2005 162:725-731Google Scholar

19 Stefurak TL, Mayberg HS: Cortical-limbic-striatal dysfunction in depression: Converging findings in basal ganglia diseases and primary affective disorders, in Mental and Behavioral Dysfunction in Movement Disorders. Edited by Bédard MA, Agid Y, Chouinard S, et al. Totowa, NJ, Humana Press, 2003, pp 321-338Google Scholar

20 Morris M: Psychiatric aspects of Huntington’s disease, in Huntington’s Disease, vol 22. Edited by Harper PS. London, WB Saunders, 1991, pp 81-126Google Scholar

21 Folstein SE, Abbott MH, Chase GA, et al: The association of affective disorder with Huntington’s disease in a case series and in families. Psychol Med 1983; 13:537–542Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22 Pflanz S, Besson JAO, Ebmeier KP, et al: The clinical manifestation of mental disorder in Huntington’s disease: a retrospective case record study of disease progression. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1991; 83:53–60Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23 Bird TD: Outrageous fortune: The risk of suicide in genetic testing for Huntington’s disease. Am J Hum Genet 1999; 64:1289–1292Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24 Wells KB, Burnam MA, Rogers W, et al: The course of depression in adult outpatients: results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:788–794Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25 Di Maio L, Squitieri F, Napolitano G, et al: Onset symptoms in 510 patients with Huntington’s disease. J Med Genet 1993; 30:289–292Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26 Zappacosta B, Monza D, Meoni C, et al: Psychiatric symptoms do not correlate with cognitive decline, motor symptoms, or CAG repeat length in Huntington’s disease. Arch Neurol 1996; 53:493–497Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27 Weigell-Weber M, Schmid W, Spiegel R: Psychiatric symptoms and CAG expansion in Huntington’s disease. Am J Med Genet 1996; 67:53–57Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28 Nehl C, Ready RE, Hamilton J, et al: Effects of depression on working memory in presymptomatic Huntington’s disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2001; 13:342–346Link, Google Scholar

29 Marder K, Zhao H, Myers RH, et al: Rate of functional decline in Huntington’s disease. Huntington Study Group. Neurology [erratum appears in Neurology 2000; 25;54:1712]Google Scholar

30 Penney JB Jr, Young AB, Shoulson I, et al: Huntington’s disease in Venezuela: 7 years of follow-up on symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals. Mov Disord 1990; 5:93–99Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31 Bamford KA, Caine ED, Kido DK, et al: A prospective evaluation of cognitive decline in early Huntington’s disease: functional and radiographic correlates. Neurol 1995; 45:1867–1873Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32 Kirkwood SC, Su JL, Conneally PM, et al: Progression of symptoms in the early and middle stages of Huntington disease. Arch Neurology 2001; 58:273–278Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33 The Huntington Study Group: Unified Huntington’s Disease Rating Scale: reliability and consistency. Mov Disord 1996; 11:136–142Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34 Benton AL, Hamsher K. Multilingual Aphasia Examination Manual. Iowa City, University of Iowa, 1978Google Scholar

35 Smith A: Symbol Digit Modalities Test Manual. Los Angeles, Calif, Western Psychological Services, 1973Google Scholar

36 Stroop JR: Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. J Exp Psychol 1935; 18:643–662Crossref, Google Scholar

37 Shoulson I, Fahn S: Huntington’s disease: clinical care and evaluation. Neurology 1979; 29:1–3Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38 Mayberg HS: Depression and frontal-subcortical circuits: focus on prefrontal-limbic interactions, in Frontal-Subcortical Circuits in Psychiatric and Neurological Disorders. Edited by Lichter DG, Cumming JL. New York, Guilford, 2001, pp 177-206Google Scholar

39 Bremner JD, Vythilingam M, Vermetten E, et al: Reduced volume of orbitofrontal cortex in major depression. Biol Psychiatry 2002; 51:273–279Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40 Mayberg HS, Starkstein SE, Peyser CE, et al: Paralimbic frontal lobe hypometabolism in depression associated with Huntington’s disease. Neurology 1992; 42:1791–1797Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41 Mayberg HS, Starkstein SE, Sadzot B, et al: Selective hypometabolism in the inferior frontal lobe in depressed patients with Parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol 1990; 28:57–64Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42 Alexander GE, DeLong MR, Strick PI: Parallel organization of functionally segregated circuits linking basal ganglia and cortex. Annu Rev Neurosci 1986; 9:357–381Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43 Alexander GE, Crutcher MD: Functional architecture of basal ganglia circuits: neural substrates of parallel processing. Trends Neurosci 1990; 13:266–271Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44 Vonsattel JP, Myers RH, Stevens TJ, et al: Neuropathological classification of Huntington’s disease. J Neuropath Exp Neurol 1985; 44:559–577Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar